Commercial vs. Industrial Applications: Focus on Cold Applications

Insulation application types can be divided into many categories. One way to define them is by market: residential, commercial, or industrial. For the purposes of this article, the comparison will be limited to commercial versus industrial. How would a contractor approach these applications differently from a materials, quote, or labor standpoint? Focusing specifically on cold applications, this article will zero in on below-ambient-temperature applications.

How Are Commercial and Industrial Applications Defined?

First, what are some examples of commercial and industrial applications? Typical commercial applications include strip malls, office buildings, hospitals, schools, churches, hotels, condominiums, supermarkets, ice rinks, and maybe even light manufacturers. Common industrial applications include manufacturing, food processing or storage, chemical, petrochemical, and power plants. Contractors tend to classify themselves as either commercial or industrial based on the type of projects they work on most. Industrial contractors may bid on commercial work when the industrial sector slows down, but most commercial contractors stay predominately within their main area of expertise. Commercial work tends to track the economy and be fairly stable, while industrial projects tend to be based on longer-term economic projections and needs, and tend to be more cyclical (feast or famine). Once allocated, they progress regardless of current conditions.

The distinction between commercial and industrial contractors is fairly clear. However, as contracting firms become larger and their need for business grows, the distinction may blur.

Often, the perception of industrial applications is that they represent mostly “hot” insulation work. Although industrial applications may have more hot work (it is estimated that 75 percent of industrial work is hot), there are certainly plenty of industrial applications that involve cold water, chilled water, refrigeration, and cryogenic applications, too. From a temperature standpoint, industrial applications cover a wider range than commercial: Below-ambient industrial applications can go from 50° to -300°F or below, while commercial work stops around -10°F. With more extreme temperatures, industrial work often involves multilayer insulation because of the thickness requirements and additional vapor barriers needed to prevent condensation or ice formation. Industrial applications also may exhibit much greater temperature cycling, which can create issues with both the insulation and jacketing.

From a performance standpoint, industrial and commercial applications attempt to accomplish the same goals:

- Reduce heat gain

- Save energy

- Reduce emissions

- Prevent condensation

- Improve equipment performance

- Improve process performance

- Reduce water consumption

- Improve personnel protection

- Control sound

- Provide freeze protection

The thermal dynamics are the same for commercial and industrial applications.

Besides temperature range, other distinctions between commercial and industrial applications include the expectations or requirements for weather resistance, chemical resistance, corrosion resistance, pipe sizes, and longevity. Commercial jobs are probably new construction and predominately indoor applications, whereas industrial projects are often retrofit or plant expansion work, with an approximate outdoor-to-indoor ratio of 60-to-40. These factors tend to make industrial jobs much more complicated. Labor and jacketing selection are key factors as well. As Ray Stuckenschmidt of Systems Undercover, Inc., notes, “When you are dealing with industrial jobs, you have to really know what you are doing.”

Commercial jobs are easier to access, the work is not as congested, and there is less need for secondary jacketing, which allows the insulation to be applied more efficiently. On the other hand, commercial work often is released in stages as a job progresses. For example, condominium projects may be released as floors are finished, so the total time to complete the work may be much longer than that of an industrial job where the time frame is tighter because the job must be completed during a shutdown period. Some industrial jobs are bid on a time-and-materials or a cost-plus basis, which would not typically be the case on the commercial side. Industrial jobs must be bid with more contingency factors built in because of the variables that may be associated with the job. The safety record of a company is also very important when bidding for an industrial job, whereas that might not be a key component for a commercial job.

Unfortunately, many commercial jobs are submitted for bid with drawings that may be as little as 60-percent complete. “Commercial applications require a high degree of knowledge of the systems involved to ensure that the estimate is complete,” says W. Paul Stonebraker of TRA Thermatech.

Materials and Thickness Requirements

From a materials standpoint, the temperature range of commercial jobs means that the most common insulation products—such as fiberglass, polyolefin, or elastomeric materials—are usually used, although there is some overlap with the industrial jobs, which often use other materials, including cellular glass and polyisocyanurate. As changes in materials occur, they may be used in applications where they were not previously considered.

In some cases, the type of pipe material being covered may limit the type of insulation used. Minimum insulation thickness requirements will be dictated by building codes for commercial jobs, but by the building owner for industrial jobs. This means the contractor is more limited in materials for commercial jobs—there may be a couple of materials to choose from, depending on the engineering specification, but the minimum thickness will be dictated by code. Industrial owners often contact insulation contractors for input on what materials perform best. Whether the job is commercial or industrial, materials cost and ease of installation (labor) will dictate what is used. From the owner’s point of view, ease of maintenance also may be a factor in material selection.

Everyone looks for an edge that will provide a lower cost, which is where ease of installation can tip material selection one way or another.

In both industrial and commercial cases, application failure can result in major costs, so shortcuts should not be taken. Best practices must be employed. Because of project size, failures on industrial jobs may be larger, but owners are generally involved in the process and more specific about the type of insulation and installation. Since commercial work involves more contact with the public, the possibility of a lawsuit as a result of a failed job is more likely. The commercial contractor also has to be flexible and adapt to changing customer expectations that may not be as well defined as those in the industrial sector.

Consider, for example, the issue of mold and mildew. Paul Sawatzke of Enervation, Inc., points out that “the issue of moisture, mold, and mildew is changing the way many contractors are looking at the material selected for commercial jobs. We need to react to the needs of the marketplace.”

There may be the mistaken concept that commercial work can be taken less seriously than industrial work. One lawsuit will convince anyone that this is not the case. Being able to seal up the insulation system and keep moisture out is the key to a good below-ambient application.

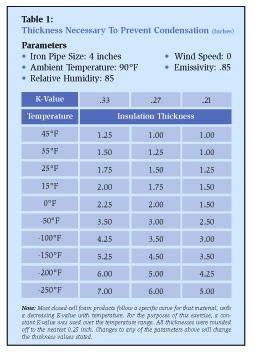

Most building codes or insulation recommendations like ASHRAE 90.1 base their insulation thickness tables on energy savings. This is due to the complexity of the tables necessary to account for all of the variables that affect energy savings, condensation formation, and the liability associated with a recommendation if it results in a failed application. However, the thickness needed to prevent condensation is often greater than the reference tables suggest. Figure 1 can be used to compare materials with different K-values to determine the thickness needed to prevent condensation for a given set of conditions. The three K-values listed represent the range of general insulation materials available.

For higher relative humidity (RH), ambient temperatures, and pipe sizes—or for lower fluid temperatures—greater thickness will be needed to prevent condensation. In conditions where the dew-point temperature is close to the ambient temperature, the surface emissivity of the insulation jacket or facing can have a major impact on the insulation thickness required for condensation control. It is recommended that 3E Plus® or a program from the material manufacturer be used to calculate insulation thickness. In addition, some materials are only available in specific sizes. As shown in Table 1, the differences in K-value are not drastically different until the temperatures become more extreme. Greater insulation thickness also means greater jacketing and pipe hanger costs.

The insulation used on a job is only part of the cost. This is particularly true of outdoor applications that must be jacketed. Jacketing provides a variety of functions, such as weather protection (including protection from ultraviolet rays); moisture and moisture vapor protection; mechanical abuse resistance; chemical resistance; added corrosion resistance; and, in some applications, fire protection. Jacketing traditionally has been aluminum, stainless steel, or polyvinyl chloride (PVC). PVC is generally limited to commercial applications.

“Because of the often required multilayered insulation and jacket requirements, industrial jobs are more technical and require a very skilled work force. I would take industrial jobs over commercial jobs every day,” says Steve Isler of Old Dominion.

The Bottom Line

So how do commercial and industrial applications compare? Surprisingly, most contractors’ opinions on the topic are very consistent. First, it is evident that commercial contractors like to do commercial work and industrial contractors like to do industrial work. Each believes their sector of the business is the best in which to operate. Because of temperature extremes and environmental factors, industrial applications tend to be more complex, which limits the number of contractors bidding on such projects. For these applications, contractors seek out the materials and practices that provide the lowest cost and fastest installation, and give them an edge in quoting and providing reliable systems that meet the technical requirements of the job. This may be in the insulation itself, the jacketing, or the installation practices.

What does the future of commercial and industrial work look like? Peter J. Gauchel of L & C Insulation, Inc. says, “The commercial sector is strong right now. The industrial sector is also extremely strong and appears to be set to stay that way for some time in the future, based on the work in the power industry.”

Besides work in traditional power plants, ethanol plants are popping up all over the Midwest, and the prospect of LNG terminals from New York to Seattle should keep the industrial sector strong into the future. As for the commercial sector, as long as the economy stays strong, it will do just fine. Although the commercial and industrial sectors use similar materials and practices, and may have similar problems such as skilled labor shortages, the markets are distinctly different in how they are quoted, installed, and billed. Contractors in both sectors can be proud of their work—saving energy, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and making the world run a little better, one pipe at a time.