Marvelous Things You Ought to Know About Negotiations

Here are 5 practical tips that will help make a negotiation more successful. These concepts are based on the author’s direct experience in the field as a design firm leader, conducting hundreds of negotiations.

Tip 1: Number of People to Take to a Negotiation

How many people should you bring to a negotiation? An old hit song says, “1 is the loneliest number that you’ll ever do.” This is really true. There is so much going on during a negotiation:

- Remembering your interests

- Controlling your own behavior

- Focusing on their interests

- Watching their behavior

The concept of going alone is clearly a weak idea.

What about bringing a larger group—say, 6 or 7 people? Even during a simple role-playing exercise in my FMI “Effective Negotiations” class, it is impossible to get that many people to stay on the same page. In a group that size, the entire group may not share the same interests, even though they represent 1 firm. Also, the more people you have, the more likely that someone will say the wrong thing, publicly disagree with his own team, or commit some other faux pas that detracts from the negotiation.

If your choices are to go alone or go with 6 people, the loner has the advantage over the group. The song goes on to say that, “2 can be as bad as 1; it’s the loneliest number since the number 1.”

Sending 2 people to a negotiation offers opportunities for each individual to have a better view of all aspects of the negotiation—both the substance of the discussion and the behavior—but then who is watching out for your interests?

The beauty of sending 3 to a negotiation is that 1 person can track your firm’s interests, 1 can keep track of the other side’s interests, and the third person can be the observer. It is the observer’s role to stay out of the action and watch the dynamics. The observer on your team is almost always the person to recommend a time out or a trip to the balcony. This may seem like you are sending someone along to simply sit there, but having an observer is key, as shown in the case study: The Importance of Bringing an Observer (see page 18).

Tip 2: Speed and Pacing

Have you ever sent a proposal to a client that has not responded to you for weeks or months? Suddenly, a call comes in from the client, usually on Friday at about 11:00 a.m. You have got people sitting and waiting to get to work on this project, and now the call comes and the client says, “Oh my gosh, I’m sorry I haven’t called you, but we’re ready to go. We want to start on Monday. Just take 10% off the fee and we can get this thing started.”

Have you ever had a call like this? It is a trick. They know you have people sitting and waiting. They are hoping you are so anxious to get them working that you are going to rush into an agreement without thinking and say, “Yes.”

So, what do you do in this situation? I had one of these calls from a client in another part of the state. “That’s great,” I said. “We want to get started on Monday, too. I’ll be there in 3 hours.”

“What are you coming here for?” They asked.

“Well, clearly we’ve opened up the negotiation and it’s urgent. I’ll be there in 3 hours. I’ll just run to the airport, get on a shuttle, and I’ll be there. If this is urgent and you need to start on Monday, I want to help you out.”

“Maybe we can meet next week,” they said.

“Okay, I thought it was urgent; but if you want to meet next week, that’s okay,” I said.

In the back of your mind you may be thinking, “Well, can’t I just give in on this so we can start on Monday?” But remember, it is a trick. They do not really need to start on Monday, and your response is, “No, we have to sit down and talk about this.” It may come in different forms, but it is a trick. Call them on it.

At the start of the “Effective Negotiations” class, I always ask the students to list their expectations for the class. We write them on a flip chart and hang it on the wall for the duration of the program. In one of the classes, a student said his goal was to “learn to negotiate faster.”

After going through the first day of lessons and exercises, this student walked to the front of the room, crossed out the word “faster,” and changed the goal to “learn to negotiate slower.”

One of the fundamental tactics of a positional negotiator is that of pushing to go fast during the negotiation.

[In] our section on preparation, we discuss the value of taking the time required for preparation. The value proposition we share also applies to the actual negotiation. In a negotiation, speeding up is normally a trick. The need to thoroughly consider each item, recall your preparation, focus on achieving your interest, and develop creative options takes time. The process should not be rushed. Just as in driving, in negotiations, speed kills.

Tip 3: If You Don’t Ask…

Do you know who the loser is in a self-negotiation? There is an old story about a city slicker who is out driving in the country on a Sunday afternoon. A few miles after passing a gas station, he runs over a nail and gets a flat tire. He opens the trunk but he does not have a tire iron and ends up hiking 3 miles back to the gas station. As he walks, he starts thinking, “These country gas stations are all alike. They charge you an arm and a leg for being open on Sunday.” This idea makes him a little angry. “They won’t like me anyway,” he goes on, “because I’m wearing a suit, and they’ll probably charge me extra for being from the city.” He gets even madder. The longer he walks, the angrier he gets about the outrageous amount the gas station is going to charge him to borrow a tire iron. When he finally reaches the gas station, he walks up to the startled attendant, throws money in his face, and yells, “There! And you can keep your stupid tire iron. I don’t want it anyway!”

He never even asked.

What I have learned over the years about car mechanics is that when you go in and they tell you the price, always ask them, “Can you do any better?” Nearly all of them will say, “Well, let’s see, we can take 10% off.” Or more! In the past, America had a non-bartering culture. You went to a retail store, looked at the price tag, and paid that price if you wanted the item. One of the few items where negotiation was involved was car buying, which made it one of the most hated activities in the United States. Everyone loved getting a new car, but hated having to buy it because it involved negotiating with someone who was a lot more skilled at negotiation than they were.

Today, due to many influences, Americans are slowly learning how to barter, and such negotiations are becoming more commonplace. Businesses and retail stores are now more willing to negotiate than ever before. However, if you do not ask, you will never know if

the item you are buying is negotiable.

Tip 4: Out-of-Scope Work

We have found that tremendous amounts of revenue are left behind by design professionals due to an unwillingness to request additional funds for out-of-scope work.

Architects, [contractors], and engineers have developed an extensive list of justifications for not pursuing additional services:

- We do not want to be accused of nickel-and-diming.

- We have to maintain the client relationship.

- We do not want to get into a fight.

- We forgot to define what was out of scope.

All of these excuses are symptoms of avoidance. Do you really think that the client has never had to go to one of his or her own clients at some point and say, “We’re happy to do X for you, but it falls outside our agreement and will be billed separately?” Of course not! It is a normal part of business.

An even more important consideration is this: What is the client’s Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA) for this out-of-scope item? The client probably does not have one. If you cannot negotiate a settlement over an out-of-scope item, what are the client’s alternatives?

For example, if you are designing a building and the client wants to rearrange a floor when you are well into the documentation phase, what BATNA does the client have if you clarify that this is out-of-scope and you need to negotiate a separate fee for the work? Will the client really cancel the project at this point, go back to square one, issue a new request for proposals, and hire another firm? Of course not. The client has a problem to be solved and hired you to solve it because the company felt like your firm had the best solution for its needs. The client wants to work with you—the company chose you.

A key to successfully negotiating out-of-scope items is to identify them immediately. A question to ask when an item is identified is: “How do you want to handle that?”

Normal response: “Handle what?”

“We have just been talking about an effort that is out of scope. Do you want us to:

- Submit a proposal and have it approved before we begin work?

- Send you an email that we are working on this out-of-scope item and get your written approval to proceed?

- Open a new number to track this effort?”

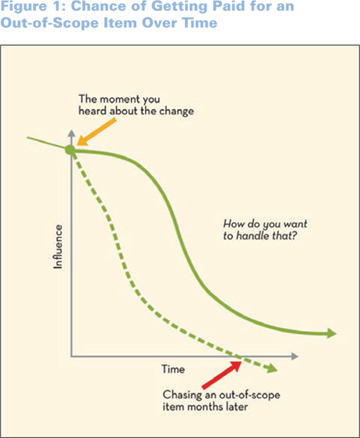

Figure 1 shows the chance of getting appropriately compensated for an out-of-scope item over time.

By the way, the concept “if we wait until later to ask for compensation, it will be better” is just plain wrong. It never works and never will. It does not hurt if you already defined how to handle out-of-scope items during your negotiation, because that is one of your interests.

Tip 5: It’s Not a Pie, It’s an Amoeba

Many negotiations books and courses talk about “making the pie bigger.” However, I do not believe this metaphor represents what happens in an interest-based negotiation.

A better way to represent a negotiation is to compare it to an amoeba.

The amoeba has a flexible shape, and its shape changes based on the direction it wants to go and where it finds the least resistance in its environment.

Similarly, a negotiation is a search for the areas of least resistance in order to expand our interests. The final shape of a negotiation is based on where both parties found opportunities to expand and necessities where they had to contract. It is not a perfectly round pie, but an irregular, organic amoeba shape determined by the discovery of mutual interests.

SIDEBAR

Case Study: The Importance of Bringing an Observer

I went with a team from my firm on a trip to China to negotiate with an organization. There was a translator working with us. The leader of my firm and the leader of the Chinese organization were speaking to each other through the translator, and I was the team observer.

As I watched the leader of the Chinese organization, it became obvious to me that he understood English. He was using the time that the translator spent explaining what we had said to come up with responses. The effect of this was that he responded to us very quickly after the translator finished, speeding up the pace and making my team feel pressured. We were struggling to come up with responses as quickly as he did, but did not have the advantage of time to think things through.

As the observer, I called a break, took my team out of the room, and explained what I had observed. They were so focused on following the conversation that they had not observed the other side closely enough to see what I saw.

We needed to shift tactics to even out the advantage of the other side, so we stopped trying to respond immediately after the translator had finished, as the other side was doing. We slowed down our responses and made sure we took adequate time to be thoughtful.

Excerpted from the new book Negotiate With Confidence: Field-Tested Ways To Get the Value You Deserve by FMI Division Manager Steven J. Isaacs. The book is available from Greenway Communications at http://store.di.net/.

Copyright Statement

This article was published in the January 2014 issue of Insulation Outlook magazine. Copyright © 2014 National Insulation Association. All rights reserved. The contents of this website and Insulation Outlook magazine may not be reproduced in any means, in whole or in part, without the prior written permission of the publisher and NIA. Any unauthorized duplication is strictly prohibited and would violate NIA’s copyright and may violate other copyright agreements that NIA has with authors and partners. Contact publisher@insulation.org to reprint or reproduce this content.