Prospects for Growth Improving, But Risks Remain: Outlook for 2012

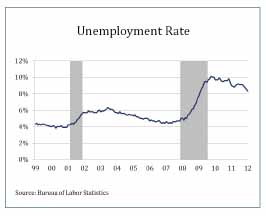

In recent months, the economy appears to be gaining some forward momentum. The job market continues to improve, housing inventories have edged down, and confidence in the recovery is cautiously growing. After meager job growth in 2010, the economy gained 1.8 million jobs during 2011 (the vast majority from the private sector) and the unemployment rate, which seemed to be stuck above 9 percent, improved substantially by early 2012. While this last point is of paramount importance to the millions of Americans still looking for work, it is also important to President Obama’s

reelection prospects, as this key economic indicator is closely linked to approval ratings. Even though employment levels remain below their pre-recession peak, improvement in private sector employment is essential to the recovery. As more Americans return to work, households become increasingly optimistic. Spending has risen, especially on durable items like cars and appliances, as some of the pent-up demand that accrued during the previous 4 years is slowly being released. Sales of light vehicles rebounded, and retail sales have strengthened. Improving job growth and confidence will propel the recovery forward in the months ahead.

In contrast to other business cycle recoveries that were led by sharply rebounding consumer spending, income growth continues to be weak as the job market remains relatively slack. Average production worker wages grew by only 2.1 percent in 2011, the slowest annual gain since 2004. This will constrain consumer spending, as households continue to bolster their balance sheets. In addition, many market watchers believe the recession brought about a new frugality among American consumers. As with the generation that survived the Great Depression, there may be a cultural shift toward less consumption relative to the decades leading to the 2008 financial crisis. This shift in consumer behavior will offset, to some degree, the pent-up demand starting to unfold.

The housing market is finally starting to show signs of life after 6 years of declines. The multifamily segment (i.e., condos and apartments) revived in 2011 as foreclosures and tight lending conditions pushed many former homeowners and new entrants into the rental market. Existing home sales have risen from their lows. Inventories of new and existing homes available for sale are returning to a balanced position. However, a steady stream of foreclosures continues to put downward pressure on home prices. In early 2012, roughly a third of existing home sales were so-called distressed properties (foreclosures and short sales), which sell at steep discounts. At the end of 2011, nearly 23 percent of all mortgages were “underwater,” suggesting defaults and foreclosures will continue to be a part of the housing landscape. On the demand side, improvements in the job market are key. During the recession, household formation?the main driver in housing demand?slumped, as unemployed young people returned to their parents’ homes and families doubled and tripled up. As employment grows, demand for housing will increase. New homebuilding will occur in areas of the country not overbuilt during the boom years and where job growth is strongest.

The industrial sector recovery continues with industrial production up and capacity utilization tightening, though at the beginning of 2012, production climbed back only about three-quarters of its peak-to-trough decline. The Conference Board’s index of leading economic indicators points to continued gains in the months ahead. Inventories are balanced against sales through the supply chain and, according to the Institute for Supply Management, many manufacturers think their customers’ inventories are too low. Order books and unfilled orders continue to expand, suggesting a broadening pipeline of manufacturing activity. A lower dollar and increasingly competitive natural gas prices in the United States have helped U.S. exports.

Despite recent gains, however, the U.S. economy remains vulnerable to a number of risks. Europe is in recession, curbing demand for U.S. exports to that part of the world. That Greece may leave the Euro is no longer considered unimaginable, and financial markets are bracing for a Greek default. Fiscal and debt problems in Italy, Portugal, and Spain also are troubling. While U.S. banks are not as heavily exposed to European debt as they were to U.S. mortgaged back securities, a disorderly unwinding in Europe could trigger another global financial crisis. In China, meanwhile, manufacturing activity in the world’s second largest economy has slowed, and property prices are sliding following a government-funded building binge. A so-called hard landing for China, while unlikely, could destabilize the global economy. Recent gains in gasoline prices also are worrisome. Higher gasoline prices act like a tax, reducing households’ discretionary spending. Longer term, deficit spending and growing U.S. Government debt may weaken growth prospects. Inopportune tax and trade policies also could threaten to derail the recovery.

Another real concern is price inflation. When growth in money supply exceeds economic growth, inflation results, as too many dollars chase the goods and services available in the market. Following the financial crisis, actions by the Federal Reserve to prop up U.S. banks resulted in unprecedented excess reserves. As of early 2012, the economy remains weak. Beyond the run up in oil prices fueled by Iran’s nuclear ambitions, there remains little evidence of broad-based inflation. However, as the economy strengthens, the Federal Reserve must be ready and able to mop up the excess liquidity in the money supply. Higher price inflation, possibly triggered by sharply higher oil prices, could seriously dampen economic growth prospects.

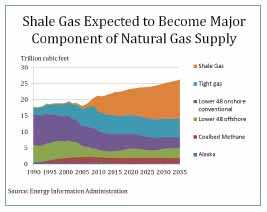

As global oil markets absorb the increased geopolitical risk from events in the Middle East and threaten global economic stability, a not-so-quiet revolution is occurring much closer to home. Natural gas production in the United States is expanding as once ignored shale gas resources are developed. This has significant implications for large segments of the U.S. manufacturing base. Shale gas is not new. The technology known as hydraulic fracturing whereby water is pumped at high pressure to create fractures in gas-containing shale rock, allowing natural gas to be extracted, has existed for decades, but was not an economic option until recently. As U.S. natural gas markets tightened in the early 2000s, and Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005 pushed natural gas prices to unforeseen highs, previously uneconomic methods for extracting natural gas from shale formations suddenly became economic. As learning-curve effects and scale economies came into play, the cost of extracting shale gas declined. The Energy Information Administration projects that natural gas production will increase by about 1 percent per year through 2035 as production from shale becomes a major supply of domestic energy.

As a result, the economics have changed significantly for a number of gas-intensive manufacturing industries, including chemicals, metals, paper, and glass. The chemical industry, in particular, is dependent on natural gas for fuel to generate the heat and pressure required to split and recombine molecules. It is also unique among industries in its use of natural gas and natural gas liquids such as ethane as feedstock for the materials it produces from ammonia-based fertilizer to ethylene, a building block molecule used in thousands of materials. A decade ago, there was little to no investment in this segment of the U.S. manufacturing base. The new economics of shale gas and natural gas liquids, however, has spurred a wave of announcements for new U.S. petrochemical capacity, as the competitiveness of U.S. petrochemicals based on natural gas feedstocks has increased. Estimates of as much as a 25-percent increase in U.S. ethylene capacity have been announced by major producers. Pipelines are being built to ship ethane from the Marcellus shale formation (in West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Ohio) to petrochemical producers in the Gulf Coast and also to Canada for use in petrochemicals. Other gas-intensive manufacturers stand to benefit as well. A recent Price Waterhouse Coopers report suggests that lower feedstock and energy costs could save U.S. manufacturers $11.6 billion annually by 2025.1 This, combined with a lower dollar, has made U.S.-based manufacturers more competitive than they have been in decades, which bodes well for a long-lasting resurgence in U.S. manufacturing.

As abundant shale gas supplies in the U.S. bolster domestic manufacturers, the export potential looms large. Roughly a dozen applications are in various stages of review to build liquefaction capacity to export liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Europe and Asia, where prices are several multiples higher than in the United States. Following the tsunami-induced nuclear disaster at Fukushima in 2011, natural gas demand in Japan has soared. In Europe, many natural gas consumers are captive to Russian supply and likely would welcome new supplies from across the Atlantic. In all, domestic shale gas resources offer tremendous opportunity for businesses along the supply chain from well head to burner tip or LNG terminal.

In summary, despite the near-term risks, the consensus outlook for the U.S. economy is for continued moderate growth. Most indicators point to steady growth, though still constrained somewhat by the excesses of the last decade. As jobs become increasingly plentiful, incomes will grow and demand for goods and services will increase, which in turn will create more jobs. Barring a shock, 2012 may be the year that the economy finally reaches the “escape velocity” that Larry Summers (former director of the National Economic Council) looked for in 2010. In the years to come, the evolving expansion will be further driven by a revitalized U.S. manufacturing sector that capitalizes on domestic shale gas resources.