The Link Between Mental Health and Workplace Safety

Despite the emphasis placed on safety, and decreases in the total numbers of deaths and most reportable injuries incurred on the job1, construction remains one of the most dangerous industries, with the Bureau of Labor Statistics reporting 986 fatal work injuries in 2021—a rate of 9.4 deaths per 100,000 full-time workers.2 At the same time, the increase in mental health issues reported across the United States is similarly reflected in the construction field. The Center for Construction Research and Training (CPWR) focused on mental health among construction workers using response data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and found that in 2020, more than one-quarter of construction workers surveyed reported feelings of anxiety at least once a month, and nearly 10% reported feeling depressed.3 While one could argue that with 2020 being the start of a pandemic, everyone felt anxious and depressed, earlier NHIS data showed that monthly levels of anxiety went up 20% from 2011 to 2018, well before Covid-19 showed up. And there is the particularly grim, often reported statistic that the suicide rate among construction workers in the United States is more than four times higher than that of the general population. Clearly, the industry has a problem with mental health issues, but is that also an overlooked aspect of workplace safety?

Certain attributes of construction work contribute to the development of anxiety and depression even in those not clinically predisposed to, and never previously diagnosed with, mental health conditions. Construction workers face the same stresses faced by those who work in other industries—such as wage concerns and job insecurity—but there are additional factors at play in construction, ranging from physical demands to a culture that prides itself on toughness. Long workdays at job sites that can be physically uncomfortable and hazardous—noisy, in extreme temperatures, often involving work in tight spaces or areas with high risk of slips and falls—become even more difficult to someone who may already be suffering chronic pain from a previous injury. Then there is the emotional strain of knowing a project is short-term, the work is seasonal, with no long term guarantee of income and, potentially, no healthcare or retirement benefits. Depending on the type and location of projects, construction jobs also may take workers away from their home and family for extended periods of time, adding another layer of stress while temporarily removing the support structure and restorative downtime that comes from spending time with loved ones. And, of course, construction work is always performed against a deadline, with progress often impacted by factors outside the worker’s control, such as weather, availability of materials, schedules that rely on the performance of other contractors, and tight budgets requiring people to do more with less. Any one of these factors can lead to on-the-job stress and burnout. Taken together, particularly if exacerbated by a corporate culture that does not place a priority on promoting worker well-being, they can result in levels of mental and physical health degradation that equate to unsafe work conditions.

If you wonder how wide scale the wellness challenge is, 2022 saw release of The U.S. Surgeon General’s Framework for Workplace and Mental Health & Well-Being, prompted in part by the staggering increase in mental health issues seen during the Covid-19 pandemic. The Framework cites the following statistics from a survey of 1,500 workers in the United States, crossing government, nonprofit, and for-profit sectors:

- 76% reported one or more mental health-related symptom, and

- 84% said “at least one workplace factor… had a negative impact on their mental health.”4

Compelling Statistics

- 2023 Workplace Safety Index data published by Liberty Mutual Insurance estimates that the construction industry in the United States loses almost $11.4 billion/year to “serious, nonfatal workplace injuries,” more than half of which (50.3%) involve falls of some type or being struck by equipment or an object.16

- $170.8 billion were lost to “preventable workplace injuries” in 2018.17

- Productivity suffers: 42% of workers whose job requires some type of manual labor surveyed reported that mental health problems kept them from achieving their goals at work in the previous month.18

- A 2016 study of the effect of depression/presenteeism/absenteeism on workplace productivity in eight countries estimated “mean presenteeism costs per person [emphasis added]… in the USA” at $5,524.00.19 Update that to 2023 dollars, consider that there are an estimated 160+ million people in the U.S. workforce20—more than 80% of whom have said conditions at their workplace contribute to mental health issues—and you can see why estimates of the cost of presenteeism in the United States range in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

How Can Mental Health Affect Physical Safety?

A host of studies have shown a correlation between mental illness and physical health problems ranging from fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and “brain fog” to headaches, high blood pressure, stomach and digestive issues, cardiovascular disease, all the way up to what is known as “all cause” mortality—that is, risk of death from any cause. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) brief reports that “depression interferes with a person’s ability to complete physical job tasks about 20% of the time and reduces cognitive performance about 35% of the time.”5 Anyone who has ever tried to work through a migraine, or struggled to focus on their work the day after a night of insomnia, has no trouble picturing how the physical and mental issues listed above can negatively affect job performance on a given day. Now imagine that it is a chronic problem, and that the worker suffering has to perform physically difficult tasks on a construction site perhaps at elevations requiring a harness, under obligation to protect others from falling object hazards—and it is easy to see how the safety risks rise exponentially.

Compounding the problem, the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) estimates that more than a third of U.S. adults suffering from mental illness also struggle with a substance use disorder6, often attempting to self-treat their condition. Many construction workers self-medicate with over-the-counter drugs to deal with pain related to the constant physical demands of their occupations, but scores also have been prescribed narcotic pain killers after being injured on the job. It is no surprise, then, that the construction industry has substance abuse rates that are nearly twice the U.S. national average—another source of safety risk7 and an acknowledged risk factor for suicidal ideation when coupled with psychological distress.8

The Dangers of “Presenteeism”

Companies recognize the dangers posed by cell phone distraction and working while under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Policies exist, and employee compliance is mandated and monitored. It can be harder to see when someone is at risk, and is putting others at risk, because they are working while unwell or otherwise disengaged. Most people are familiar with the concept of “absenteeism,” which is when people miss work. Fewer have heard of “presenteeism,” the term used to describe when workers show up despite illness. They could have obvious symptoms of disease, such as coughing and sneezing, and are reporting to work because they have run out of sick days and cannot afford to take unpaid leave, or they know their coworkers will be hard pressed to make a deadline without them, for example.

Other cases of presenteeism are harder to spot, and they may represent a greater threat. Coworkers who see someone coughing will know to keep their distance if they want to stay healthy. Workers who are emotionally or mentally disengaged are harder to spot. As the popular commercials for antidepressants depict, many people who are suffering on the inside put up a brave face on the outside, and this can be particularly true on job sites that are still predominantly male and where, regardless of gender, individuals can be loath to show weakness.

Living (and working) with the pain of mental illness is tragic in itself. It is even more tragic to realize that injuries or deaths are occurring across the country that are absolutely preventable if the work environment and corporate culture promoted wellness.

Achieving Workplace Well-Being

Workplace well-being expert, international public speaker, and author of Workplace Wellness that Works Laura Putnam has written and spoken widely on the importance of employee well-being not only to the individual worker but also to the entire organization. She notes that the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 “is not called the Occupational Safety OR Health Act,” emphasizing that “safety and well-being, particularly mental well-being, go hand in hand. You can’t have one without the other.” She adds, “It’s very intuitive but somehow has been separated out.”

Putnam notes that just as we’ve seen with workplace safety, the conversation about health and well-being is starting to shift to a discussion about culture and environment. She adds that while the solutions offered to address mental health issues are still individually oriented for the most part—e.g., access to counseling through an Employee Assistance Program—research overwhelming suggests that the rising rate of issues like burnout, despair, loss of purpose, and hopelessness often have more to do with the workplace itself and less to do with the individual. She references Douglas Conant and the remarkable story of how he turned around Campbell Soup in the 2000s.

Additional Information and Resources

Call: 1-800-662-HELP (4357)

If you are in crisis, please call or text 988.

Resources for Employers

- NIOSH Total Worker Health Program: www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/default.html

- OSHA References:

• Guidance and Tips for Employers on Workplace Stress: www.osha.gov/workplace-stress/employer-guidance

• Field Safety and Health Management System Manual – Chapter 10. Violence in the Workplace: www.osha.gov/shms/chapter-10 - SHRM Workplace Bullying Policy information: www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/tools-and-samples/policies/pages/workplace-bullying.aspx

More Information on Workplace Bullying/Harassment

- Workplace Bullying: What Can You Do? www.monster.com/career-advice/article/workplace-bullying-what-can-you-do

- OSHA Workplace Violence: https://www.osha.gov/workplace-violence

- Workplace Bullying Institute: https://workplacebullying.org

Learn More about Suicide Prevention

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: https://988lifeline.org

- The Construction Industry Alliance for Suicide Prevention: https://preventconstructionsuicide.com

- The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention – A Construction Industry Blueprint: Suicide Prevention in the Workplace: https://tinyurl.com/3whf585w

- The Center for Construction Research and Training Suicide Prevention Resources: https://tinyurl.com/53v8zbrf

- Anxiety and Depression Association of America – Prevention and Warning Signs: https://tinyurl.com/yc32tzdr

If You Need Help

- National Institute of Mental Health: www.nimh.nih.gov/health/find-help

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s free, confidential, 24x7x365 National Helpline: https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/national-helpline

In 2001, when Conant took the helm as CEO, the Campbell Soup Company was in disarray:

declining sales, market value dropped in one year by 54%, and a workforce demoralized by layoffs and a toxic environment described by one Gallup manager as “among the worst [he had] ever seen among the Fortune 500.”9 Conant worked with executive leadership to address the corporate culture by creating The Campbell Promise: “Campbell valuing people. People valuing Campbell.”10 Valuing people came first in the promise, and Conant underscored that by emphasizing civility, modeling that behavior and replacing senior leaders who were unable or unwilling to adapt to his approach. Putnam says, “On Day 1, he told people across the organization that he was going to be tough minded on standards and tender hearted with people. The way he went about doing this is he focused on his daily touchpoints. Meetings, hallways, cafeterias, he made an intentional effort to handle each of those touchpoints well, even if it was a moment, to help that employee feel valued.” She adds, “Doug wrote personally hand written thank you notes—it’s estimated he wrote more than 30,000 personally hand written thank you notes… He thought the only way to turn around performance was to turn around culture first: lifting people’s spirits up every day. [It’s] foundational to performance and to safety.” During Conant’s tenure (2001 to 2011), Campbell turned itself around, receiving Gallup’s “Great Workplace Award” 4 years in a row. In the process, Conant proved that culture of civility is good for both employees and the bottom line: 2 years after he began his tenure, in fiscal 2003, net earnings grew 14%11; and by 2009, Campbell was outperforming the S&P 500.12

Putnam contrasts Conant’s leadership style with the bullying style of leadership seen at jobsites and in offices across many industries, including construction. She describes a scenario that is all too easy to picture: “Let’s say you have a safety meeting, and you’ve got a team that gets humiliated by a tough boss who mocks them openly. They’re not going to be as focused throughout the day. They’ll be thinking of that moment [that they were humiliated] throughout the day.” So, that day, both productivity and safety will be compromised across the team. And if that toxic boss behaves that way all day, every day, it will take a toll on employee well-being, productivity, and safety long term.

Putnam emphasizes that companies need to drive the culture of well-being from the top—the “trendsetters,” as she calls them (think of Douglas Conant’s example). Next are the front-line managers, the “permission givers.” They’re the ones who have the greatest influence on behavior. Putnam explains, “If you have dispersed sites, the influence that trendsetters have on remote sites is less, [while] the influence that direct supervisors/permission givers have is greater.” She adds, “Even if you are in headquarters, your day-in and day-out culture is largely what you experience in your team, so those permission givers/managers are not only key to mental well-being… but also chief architects of culture for the people on their team.” Putnam stresses that every manager and supervisor “needs to understand why well-being matters, and how it ties to safety and every metric that matters.”

Putnam references the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Total Worker Health® (TWH) Program. The program’s roots go back to a 2004 NIOSH-sponsored

symposium, Steps to a Healthier U.S. Workforce, and it has evolved considerably since then. As described on the NIOSH website:

Total Worker Health® is defined as policies, programs, and practices that integrate protection from work-related safety and health hazards with promotion of injury and illness-prevention efforts to advance worker well-being. The Total Worker Health (TWH) approach seeks to improve the well-being of the U.S. workforce by protecting their safety and enhancing their health and productivity. Using TWH strategies benefits workers, employers, and the community.13

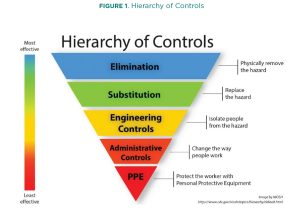

Many in construction are familiar with the standard CDC/NIOSH Hierarchy of Controls

(Figure 1), which lists an order of actions to reduce/remove workplace hazards.

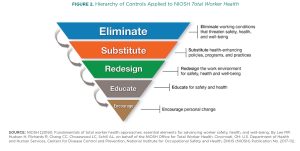

People are less familiar with the “Hierarchy of Controls Applied to NIOSH Total Worker Health,” a companion to the original model that features strategies specifically targeted at advancing well-being (Figure 2). As with the traditional version, the strategies appear in order of effectiveness, beginning at the top.

As is clear from Figure 2, addressing the issue of well-being at the individual level is the least effective solution. Conditions that threaten worker wellness must be identified and eliminated at the top—the environmental/cultural level—with changes driven down through the organization.

Call to Action

According to the National Safety Council (NSC), the construction industry experienced 4,472 preventable fatal injuries—the highest number across industry sectors.14 Most readers of this magazine have defined safety policies and a safety plan that identifies potential hazards and defines corresponding mitigation activities. Project safety plans typically include elements like a detailed description of the project scope, site conditions, hazards, job site rules and standards, safe practices, crisis and emergency plans, a list of people responsible for the project, and more. The plans are living documents, updated as new requirements and conditions appear. This focus on safety is vital, but such safety plans focus largely on external items—physical dangers, hazardous materials, procedures to be followed. What is your company doing to address the issue of workplace stress and worker well-being, to influence the internal factors that can have a tremendous impact on how safe your jobsites are? Did you know that OSHA’s Field Safety and Health Management System Manual includes a chapter on providing “a workplace that is free from violence, harassment, intimidation, and other disruptive behavior”15 (Chapter 10, Violence in the Workplace)? Does your company have an anti-harassment/anti-bullying policy statement? If so, is it enforced?

If you have an Employee Assistance Program and health insurance benefits that cover mental health issues, that is an important first step. Beyond that, though, consider whether your corporate culture supports open dialogue and acceptance of issues surrounding mental wellness. What is the environment like in your office(s) and on jobsites?

When you consider the human cost of preventable injuries and deaths, as well as what they mean for your business, it is certainly worth looking into what can be done to support worker well-being in your organization.

Citations:

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, in cooperation with state, New York City, District of Columbia, and federal agencies, Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries. Modified December 16, 2022. Accessed at www.bls.gov/news.release/cfoi.htm#

- www.bls.gov/charts/census-of-fatal-occupational-injuries/number-and-rate-of-fatal-work-injuries-by-industry.htm

- Brown, Samantha, MPH, Amber Brooke Trueblood, DrPH, William Harris, MS, Xiuwen Sue Dong, DrPH, “Construction Worker Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic, CPWR – The Center for Construction Research and Training Data Bulletin, January 2022, accessed at https://www.cpwr.com/wpcontent/uploads/DataBulletin-January2022.pdf

- The U.S. Surgeon General’s Framework for Workplace Mental Health and Well Being, 2022, accessed at www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/workplace-mental-health-well-being.pdf. See also Mind Share Partners, 2021 Mental health at work report—the stakes have been raised (www.mindsharepartners.org/mentalhealthatworkreport-2021)

- “Mental Health in the Workplace, CDC, July 2018, citing Lerner D, Henke RM, “What does research tell us about depression, job performance, and work productivity?” in J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(4):401–410. accessed at www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/tools-resources/pdfs/WHRC-Mental-Health-and-Stress-in-the-Workplac-Issue-Brief-H.pdf

- “Mental Health By the Numbers,” NAMI, updated April 2023, accessed at https://www.nami.org/mhstats

- Kaliszewski, Michael, PhD, “Construction Workers & Addiction: Statistics, Recovery & Treatment,” American Addiction Centers, updated July 24, 2023, accessed at https://americanaddictioncenters.org/workforce-addiction/blue-collar/construction-workers

- Xiuwen Sue Dong, DrPH, Raina D. Brooks MPH, Samantha Brown MPH, William Harris, MS, “Psychological distress and suicidal ideation among male construction workers in the United States,” American Journal of Industrial Medicine, Volume 65, Issue 5, May 2022, pages 395–408, accessed at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajim.23340

- Porath, Christine, and Conant, Douglas R., “The Key to Campbell Soup’s Turnaround? Civility” Harvard Business Review, October 5, 2017, accessed at https://hbr.org/2017/10/the-key-to-campbell-soups-turnaround-civility

- Ibid.

- Schnorbus, Roger R., “Campbell Soup Company in 2004 (A),” Virginia: Richmond, 2004.

- Duncan, Rodger Dean, “How Campbell’s Soup’s Former CEO Turned The Company Around,” Fast Company, 09-18-14, accessed at www.fastcompany.com/3035830/how-campbells-soups-former-ceo-turned-the-company-around

- “NIOSH Total Worker Health® Program,” accessed at www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/default.html

- NSC analysis of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI), accessed at https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/work/work-overview/work-safety-introduction.

- See www.osha.gov/shms/chapter-10.

- https://business.libertymutual.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/WSI_1002_2023.pdf

- NSC 2020 data reported in “Making the Business Case for Total Worker Health®”, NIOSH/CDC website, accessed at www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/business.html

- “The American workforce faces compounding pressure: APA’s 2021 Work and Well-being Survey Results,” American Psychological Association, 2021, accessed at www.apa.org/pubs/reports/work-well-being/compounding-pressure-2021

- Evans-Lacko S, Knapp M., “Global patterns of workplace productivity for people with depression: absenteeism and presenteeism costs across eight diverse countries.” Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016 Nov;51(11):1525-1537. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1278-4. Epub 2016 Sep 26. PMID: 27667656; PMCID: PMC5101346.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Economic News Release, “Table A-1. Employment status of civilian population by sex and age” (Aug. 2023), accessed

at www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t01.htm#