A World of Possibilities

U.S. Gas Fundamentals

While the United States is the world’s second largest natural gas producer after Russia, it is also the world’s largest natural gas consumer and importer. As of 2004, U.S. natural gas production and consumption stood at approximately 18,500 billion cubic feet (Bcf) and 22,400 Bcf, respectively.

Natural gas constitutes approximately 23 percent of America’s energy consumption. Most gas consumed domestically is produced in the United States or Canada, but these existing supplies are insufficient in the face of growing demand.

North America, and in particular the United States, requires additional sources of energy to meet expected increases in demand over the decades to come. While it is commonly known that the United States has imported the majority of its crude oil for some time, it is a lesser-known fact that U.S. natural gas production has been unable to keep pace with domestic demand and that incremental increases in natural gas imports from Canada are not expected to offset future demand growth.

U.S. imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in 2005 were relatively unchanged from 2004 levels, but import totals for 2006 were around 830 Bcf. In 2007, U.S. LNG imports are expected to be more than 1 trillion cubic feet (Tcf).

Prior to 1999, Algeria was almost the sole provider of LNG to the U.S. market. However, freight economics dictated the shift in supply to Trinidad and Tobago when LNG production commenced there. Today, over 70 percent of U.S. LNG imports come from Trinidad and Tobago.

In an effort to diversify sources of LNG supply, U.S. importers now procure product from Nigeria and the Middle East, but the majority of LNG arriving at U.S. terminals continues to originate in Trinidad and Tobago.

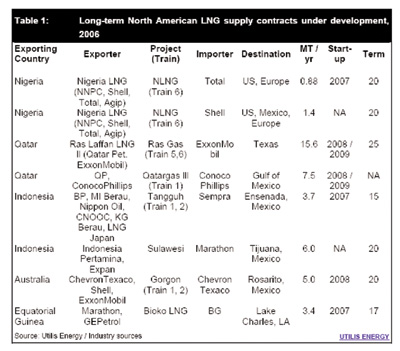

Further supply diversification is expected to occur over the next few years. The table below details long-term LNG supply contracts in various states of development with producers in Indonesia, Australia, and Equatorial Guinea. These supplies of LNG are the main sources that constitute the rapid regasification terminal expansion in the United States.

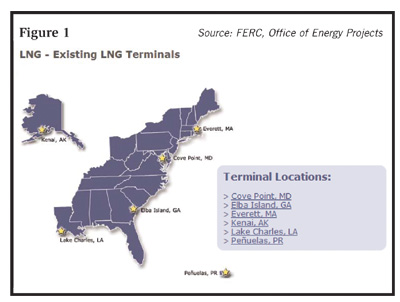

Such market fundamentals, in addition to recent price increases, create a favorable environment for increased imports of LNG, which amounted to 652 Bcf—roughly half the expected future demand—in 2004. However, greater reliance on LNG is stymied by the lack of sufficient capacity at U.S. regasification terminals. There are only five such import terminals currently in operation in the United States, and regulatory hurdles and opposition from both public and private bodies have hindered the construction of additional regasification infrastructure.

The five U.S. import terminals are operating in the following locations:

- Everett, Massachusetts

- Cove Point, Maryland

- Elba Island, Georgia

- Lake Charles, Louisiana

- Penuelas, Puerto Rico

Technology for Tomorrow

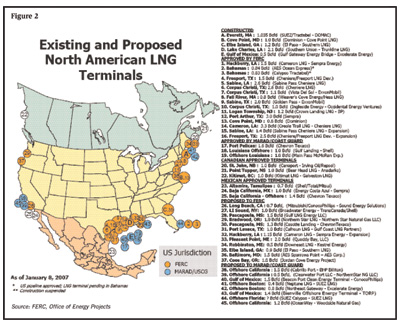

The LNG market in the United States underwent a fundamental change in August 2005, when President George W. Bush signed the Energy Policy Act. This clarified the federal government’s role in choosing sites and overseeing operation of onshore and near-shore LNG import terminals, and gave the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) ultimate authority over states on LNG issues.

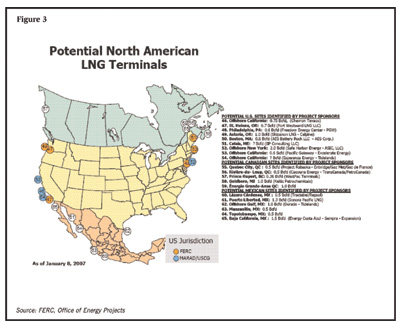

By the end of 2005, the FERC had approved 12 LNG terminals, and the U.S. Coast Guard had approved 2. Most of these proposed LNG terminals will be located in the Gulf of Mexico, resulting in relatively little opposition from a region already accustomed to abundant petroleum industry infrastructure. Twenty more facilities are currently proposed. Of these, 12 will be under the authority of the FERC and 8 will be offshore and under the authority of the Coast Guard.

To facilitate the importation and regasification of LNG, there has been a rapid expansion in the range of alternative offshore LNG importation methods. These new methods are expected to compete with conventional onshore regasification terminals.

The following concerns shared by individuals, communities, and governments act as the catalyst for alternative, offshore LNG regasification:

- Environmental issues. One of the most appealing features of offshore LNG import terminals is their lack of environmental impact on shorelines and population centers. An offshore LNG import terminal is a relatively small and isolated installation; in the unlikely event of an accident, few would be affected.

- Security and safety issues. The enhanced security and safety of offshore LNG infrastructures is a result of the remoteness of these facilities. Access to offshore LNG sites can be monitored and restricted to a much greater extent than access to onshore installations.

- Regulatory issues. U.S. offshore LNG facilities are under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Coast Guard—not the FERC. This is positive, because the Coast Guard seems to be both less bureaucratic and more efficient. For example, the U.S. Coast Guard approves LNG project applications in 1 year, while it usually takes the FERC 18 months or more to approve an onshore facility.

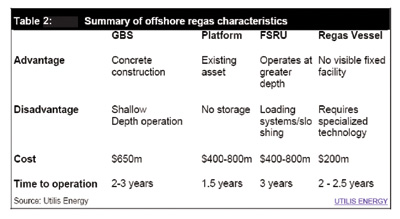

Offshore receiving technologies can be defined by the following categories:

- Offshore gravity-based structures (GBS). A GBS LNG import terminal consists of concrete or steel caissons on the seabed. This type of installation is completely self-supporting with respect to its operation, utilities, and power generation.

- Platform-based import terminals. These terminals utilize existing oil and gas platform structures, converting them to accommodate LNG deliveries.

- Floating storage regas units (FSRU). An LNG import terminal concept consists of a purpose-built, permanently moored steel structure with LNG carriers shuttling between an export facility and the import site.

- Regasification vessels. A standard LNG carrier is modified to enable the vessel to discharge regasified LNG to a subsea pipeline through an internal turret arrangement connected to an offshore mooring buoy.

Each of these offshore regasification technologies has its own merits and disadvantages. Determining which technology to use is highly dependent on various environmental factors, including water depth and other logistical factors.

Expanding Terminals, Expanding Possibilities

On June 15, 2006, the FERC approved a number of filed applications to develop new liquefied natural gas (LNG) import facilities in the United States. These projects included the following three new facilities, plus expansions on two existing U.S. facilities:

- Creole Trail LNG and Creole Trail Pipeline

- Port Arthur LNG and Port Arthur Pipeline

- Crown Landing LNG Project

- Sabine Pass

- Dominion Cove

If the facilities above are brought online, they will increase U.S. LNG import capacity to 8.2 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d), and eventually to 9.7 Bcf/d.

LNG was once considered too expensive for the American market, but because of rising natural gas prices and falling LNG production and delivery costs, the fuel is an increasingly viable and potentially profitable source of energy for the North American market. However, since U.S. import capacity is currently insufficient to meet projected U.S. forward demand, additional regasification facilities are required to bring additional supplies to market.

The industry has expressed concern that companies active in the market are running the risk of overbuilding import-terminal capacity, creating a potential oversupply in the market that will eventually depress gas prices and impede operating profitability. This concern is compounded by the fact that the combined production capacity of all North American LNG projects currently on the drawing board exceeds 75 Bcf/d of gas. In 2004, the entire global LNG business averaged only 18 Bcf/d. It is therefore inevitable that many import-terminal projects will fall by the wayside, while others will likely be rejected during the permitting process.

Many see the expansion of U.S. LNG imports as a way to lessen U.S. dependence on foreign oil, and they welcome the expansion plans. Still others oppose any new LNG import terminal developments, citing the potential threat posed by terror groups and environmental disruption. These factors contribute to the complexity associated with the billions of investment dollars required to construct new LNG import and regasification facilities.

Evolving LNG market fundamentals, regulatory changes within the U.S. government, and innovative offshore regasification technologies are setting the stage for a promising future for LNG imports into the United States. These imports will play a significant role in helping the United States greater diversify its sources of global energy supply. It is an exciting, though challenging, time in the energy industry. With a growing global LNG market, there are definitely new expansion opportunities for businesses in the United States, and around the world.

This marketplace analysis of the potential for LNG terminals in the United States shows the possible impact LNG will have on the future of the energy industry. New U.S. import-terminal projects could create opportunities for the overall construction marketplace, as well as the mechanical and industrial insulation industry.

Stay tuned for upcoming articles in our March/April State of the Industry issue that cover the opportunities in the overall insulation marketplace. Also, read the upcoming June Insulation Outlook to learn more about insulation’s role in building an LNG system.

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of over 60 LNG facilities in operation or in various stages of planning and development in North America. The review included the following: participant and company contact information; a description of the project and its main features; anticipated operating capacities; expected sources of supply; date or expected date in service; status of regulatory approvals; and breaking project news and recent developments. To learn more about this report, please go online and visit www.utilisenergy.com.

Editor’s note: The opinions and information shared by the author in the preceding article have not been confirmed, nor are they endorsed, by the NIA.