Going to Extremes: The New Museum Runs Both Hot and Cold

Imagine a building designed not only to shelter people and materials but to give visitors realistic exposure to locations and events they likely will never experience firsthand, “immersing” them in a range of physical and emotional landscapes so affecting that they lose track of their true environment. Now imagine that the same building is designed and constructed to be forward-looking, incorporating innovative sustainable design features that clearly place it in the realm of the future even as it honors the past. The brand-new National Museum of the Marine Corps—dedicated November 10, 2006, and opened to the public on November 13—is such a building. This article, the first in a two-part series on the new museum, discusses elements of the design that create the immersive experience for visitors. The second article will explore the building’s green design features.

Located on 135 acres adjacent to the U.S. Marine Corps Base at Quantico, Virginia (about 35 miles south of Washington, D.C.), the museum’s mission is to “explore the values, mission, and culture of the Marine Corps through state-of-the art exhibits, world-class contemporary architecture, and compelling subject matter,” according to the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation.(1) Denver-based architectural firm Fentress Bradburn Architects, Ltd., won a national competition to design the museum, developing a unique building that meets the Foundation’s goal. Under one roof, visitors experience exhibits that lead them through boot camp, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. In the latter two exhibits, the galleries are actually climate controlled to make the visitors’ experience that much more realistic. Even the museum’s restaurant is vintage Marines—a re-creation of Tun Tavern, known as the birthplace of the Marines.

While the end result is spectacular, designing and constructing a building of “world-class contemporary architecture” capable of supporting significant differences in climate from one exhibit to the next (both in terms of temperature and humidity), while meeting goals of sustainable design to conserve energy and reduce long-term operating costs, certainly presents challenges.

A Building With a Strong Identity

Even before visitors get inside the museum, they can feel strength emanating from the museum’s bold, dramatic appearance. The building’s exterior resonates strongly with the Marine identity. Primary building materials—cast-in-place concrete, metal, and glass—were selected by the architects to represent the Marine Corps’ values of honor, courage, and valor. The most striking feature is a 210-foot tilted mast that rises from the building’s 160-foot glass atrium roof. Rising at a 60-degree angle and clearly visible to all who drive on nearby Interstate 95, the mast is intended to evoke the image of the Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima during World War II, captured in the famous photo by Joe Rosenthal. The appearance of the atrium and spire also draws comparisons to bayonets or swords raised, the angle of a jet on takeoff, and Howitzer cannons.

Designing an Immersion Experience

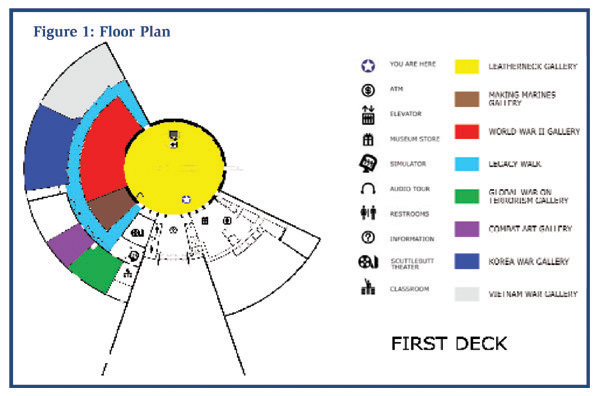

To develop a feel for what it is like to be a Marine, members of the design team (some from Fentress Bradburn and others from Christopher Chadbourne and Associates, a Boston-based exhibit design firm) first immersed themselves, visiting sites of historic battles, sleeping in troops’ quarters, and participating in a week’s worth of boot camp in San Diego at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot. The result is a design that incorporates a 35,000-square-foot entrance area at the center of a ring of galleries. An additional 85,000 square feet of exhibits incorporate historical artifacts, multimedia presentations, and immersive sets to give visitors an understanding of Marine culture as well as exposure to Marines’ role and experiences in various conflicts making up the Corps’ proud 231-year history. Figure 1 provides a look at the museum’s floor plan. The central Leatherneck Gallery is some 45 feet tall to accommodate suspended Marine aircraft and additional large artifacts. The gallery’s stone walls, engraved with moving quotations, feature eight enormous (12- x 9-foot) photos of individual Marines. The terrazzo floor gives one the impression of sea, especially dramatic under the huge, skylit ceiling.

While the Leatherneck Gallery and other areas of the museum rely primarily on visual and auditory cues—such as the boot-camp experience where, among other activities, visitors can fire laser M-16 rifles—the most immersive galleries are those that also use temperature and humidity to affect visitors.

The Korean Chosin Reservoir exhibit is set at 58°F (see Photo 2), not as cold as the actual winter conditions (about -20°F) some 250 Marines encountered as they defended the Toktong Pass supply route from Chinese soldiers for 5 days in 1950. Museum visitors will feel the drop in temperature clearly as they pass through glass doors into the exhibit. That feeling, combined with the sight of simulated flares and the outlines of Chinese soldiers’ bodies in the snow, along with the sounds of shouting Marines, will help transport visitors to the harsh battlefield environment where half of the Marines in Fox Company lost their lives.

The physical setting of the Chosin Reservoir exhibit is in stark contrast to the 88°F, high-humidity environment visitors feel in the exhibit on the 1968 siege of Khe Sanh, where conditions approximate the jungles of Vietnam. The exhibit is designed to bring visitors into a critical supply and medevac mission at Hill 881-South. Visitors enter the exhibit through a CH-46 Sea Knight helicopter. As their bodies register the heat and humidity, they take in the sound of bullets hitting the metal fuselage, accompanied by shouting. Once off the helicopter, they see the life-size image of a dead Marine being tended to by a chaplain.

While the interior immersion galleries and the external design elements are moving and reflective of the Marine Corps experience and ethos, they are not particularly straightforward in terms of construction and insulation considerations.

Practical Factors in Execution Including Insulation Solutions

How are the environments maintained within the individual galleries? Charles Cannon, project architect with Fentress Bradburn, notes, “The different atmospheres are created and controlled by the mechanical system. Individual VAV (variable air volume) boxes are used to create the unique climates of the immersion galleries.” He adds that supporting the mechanical system, different types of insulation are used depending on location in the building. For below-grade interior surfaces of the immersion galleries (Type 1), the specifications called for extruded preformed cellular polystyrene insulation conforming to ASTM C 578. Elsewhere, the insulation specified was aluminum foil–faced rigid cellular polyisocyanurate, to conform to ASTM C 1289 (Type 2). Vapor permeance was set at not more than 1.1 perms for the Type 1 areas, and not more than 1.03 for Type 2 areas. Compression resistance of rigid cellular plastics was specified as not less than 15 pounds per square inch (psi) for Type 1 areas, and not less than 25 psi for Type 2 areas.

At the same time that the immersive exhibits incorporate distinct climates, the overall museum environment must be maintained at RH 50 percent to ensure preservation of the historic artifacts on display. Cannon stresses, “As this building is a museum with many priceless and one-of-a-kind artifacts, the focus was preservation.” More than 60,000 artifacts are maintained by the Marine Corps’ History and Museums Division. Of these, 5 to 10 percent will rotate on display at the museum. The artifacts range from an original flag raised on Iwo Jima to letters from Marines out in the field, as well as equipment such as a helicopter, vintage airplanes, and a M4A3 Sherman tank.

Cannon noted that overall thermal resistance is R10 for all applications. In terms of fire-protection requirements, the flame spread index is 75 or less; the smoke developed index is 450 or less throughout.

The atrium roof uses roughly two-thirds of an acre of glass in a skylight design unusual for the top of a low-rise building. Air-circulation studies were assessed how best to manage the volume of air in a space that would be difficult to heat and cool economically. To accommodate the high temperatures of summer, the design calls for a fan with controlled louvers to allow ventilation through the top of the mast. The equivalent of a 20-story building, the 210-foot mast is covered with stainless steel cladding.

The use of natural daylight is one approach to reducing the building’s long-term operating costs. According to Cannon, “Energy efficiency is always a concern of ours.” He adds that although the museum is not a LEED-certified building, the project incorporates many environment-friendly approaches, including the use of highly recycled materials such as the steel used in the structural system. (The museum’s sustainable design elements will be described in more detail in the second article in this series.)

Planning for the Future

The current exhibits—along with the adjacent Semper Fidelis Memorial Park—represent the first phase of the project. Future exhibits will enhance the historic context, going back to the Revolutionary and Civil wars, and exploring the Marines’ recent involvement in conflicts in the Balkans, Kuwait, Iraq, and Afghanistan. There are plans for an IMAX theater, offices, a small chapel for weddings and funerals, and a hotel and conference center elsewhere on the site. In anticipation of future expansion of the museum building, each exterior and interior concrete wall is a retaining wall. Museum operations won’t be interrupted for expansion, as work can begin on the other side of any of these retaining walls.

With innovative design—both inside and out—the National Museum of the Marine Corps brings history and tradition to life, living up to the message engraved over the museum’s entrance: “Enter and Experience What It Means To Be a Marine.”

The National Museum of the Marine Corps is a joint effort between the Marine Corps and the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation. For more information, visit www.usmcmuseum.org.