Maintaining the Asset That Matters Most

Rethinking worker retention in post—Baby Boom America.

Joe has been with the company for just a few months, but it is already obvious he is one of the good ones. He shows up on time, puts in an honest day’s work, and gets along well with his co-workers. He is new to the insulation business but learning fast, and it is easy to imagine him supervising his own crew in a few years.

Then one day, out of the blue, Joe puts in his 2 weeks’ notice. The new plant opening up down the road has offered him 75 cents more an hour. It doesn’t seem like much, he tells you—almost apologetically—but it adds up over time. Joe walks out of your office. You reach for the phone to call the paper and place yet another want ad.

Sound familiar? If so, you are not alone. This same scenario plays out dozens of times a day in plants and shops across the country. Worker retention is a problem—not just for the insulation industry, but for every business sector in the United States—and the problem is getting worse.

Why? The answer is easy, but it is also a bit scary for those responsible for finding enough workers to do the job.

The Baby Boom

Between 1946 and 1964, the United States experienced unprecedented population growth. The optimism following victory in World War II, the educational opportunities made affordable under the GI bill, the economic prosperity of America’s new “superpower” status, the development of suburban housing, and employment-based group health insurance have all been cited as factors in a “baby boom” that produced 76 million children in fewer than 20 years.

The first Baby Boomers—those born in 1946—turn 61 this year. Many of them are retired already, but many more are getting ready to retire. Over the next 20 years, the number of retirees each year will far exceed the number of people entering the work force. Beyond the sheer numbers of Baby Boomers leaving the work force, there is also a serious “brain drain” taking place. At the end of their careers, many Baby Boomers are the managers, supervisors, and team leaders of businesses. They take with them everything they have learned in the past 20 years about running a business and serving clients. In the industrial and mechanical insulation industry, these workers also take with them the specific insulation knowledge they have gained over the years.

The Baby Boomers were raised by the “gold watch generation”—people whose work ethic was indistinguishable from their loyalty to a single employer. The day after graduation, members of that generation went to the company in their town, got a job, and stayed for 20 years until they retired with a pension, a gold watch, and pride in a job well done.

Those days are gone.

Generation X

The Baby Boomers are the bridge between the gold watch generation and Generation X, the 44 million people born between 1965 and 1980. Generation X’s concept of employment differs from their grandparents’ in the following significant ways:

- Loyalty: A job is a job. Most people in the work force today have few expectations that their employers will be loyal to them, so they feel less loyal to their employers.

- Mobility: Go where you want to go. The post–Baby Boom work force is mobile. Workers go where the jobs are, where the weather is better, or where their friends go. The decision of where to live often is made before knowing—or even without considering—what to do once there.

- Risk-taking: Who wants to be a millionaire? Because companies are no longer perceived as taking care of their workers, many in today’s work force are willing to take chances that would have been considered irresponsible in past generations. For example, knowing the odds against a start-up company succeeding, younger workers will take a chance if it means higher pay or a chance at profit sharing.

- Stability: “Can’t keep a job” versus “can’t keep up.” It used to be that if someone had several jobs on his or her resume, the person looked flighty or—even worse—like a problem employee. Today, there is almost no such thing as too many jobs. The speed with which technology is evolving demands an equally fast evolution of skill. Ambitious workers who want the benefits that come from having in-demand skills constantly seek new opportunities for growth. This kind of thinking is at odds with that of employers who are focused on keeping skilled workers where they are, using the skills they already have, rather than encouraging their growth into different jobs.

Taking a New Approach

In the insulation industry, as in other construction trades, it is smart to focus substantial resources on training and retaining good employees. To keep the workers they want to keep, employers must change the way they think.

Employers should ask themselves, “What is the most valuable asset we’ve got?” If the answer is anything other than “our people,” it is time to think again. Regardless of what equipment is online, what orders are in the pipe, or what raw materials are sitting in the warehouse, the employees are a company’s most valuable asset. Without people to operate the machines, fill the orders, and transform raw materials into product, there would be no business.

Because the employees are a company’s most valuable asset, employers need a plan for managing that asset that goes beyond the “recruit, interview, hire, and fire” model. Fortunately, the insulation industry has a successful asset-management model on which this new approach can be based: maintenance.

Think about the most expensive piece of equipment in a company’s shop. There is, of course, a maintenance schedule for it. That piece of equipment represents a large investment for the company, and keeping it running at peak efficiency is crucial to the success of the business.

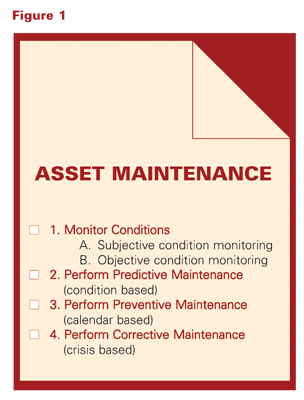

That maintenance schedule is likely to look much like Figure 1.

The original example in this article of Joe giving his notice might have ended differently with a good asset maintenance plan in place. The following is an example of how the equipment maintenance schedule could have been applied to that situation:

1. Monitor Conditions.

A. Subjective condition monitoring. Think about all the ways the condition of equipment is monitored. It begins with looking at it, listening to it, and checking the output. The same is true of monitoring employees. First, employers should look, asking themselves the following questions: 1) What does the job look like from Joe’s point of view? 2) Does he know he is valued as a good employee? 3) Does he know he has potential for advancement? 4) Does the job look like a dead end to him? Employers should take opportunities to listen to employees, whether it is in a meeting or over a cup of coffee in the break room. If they don’t ask, chances are they won’t find out what employees like and dislike about their jobs—until the day the employees quit. If employers find out what employees are thinking, however, they can use that information to create the kind of workplace where people want to stay.

B. Objective condition monitoring. Every personnel office has a great record-keeping system for tracking the workers hired, but how well do they track the workers who leave? Joe said he is leaving for a better paying job, but is that the whole story? There is an old saying that “people don’t leave companies, they leave bosses.” Could there be more to this than money? Tracking supervisors who are best at retaining workers can be very informative. The highest quality supervisors can share their knowledge on asset maintenance with other supervisors to improve employee retention throughout the company.

2. Perform Predictive Maintenance.

What about that plant opening up just down the road? Joe knew about it. Did his employer? Of course they did, but because the new plant is not a competitor’s (that is, it will not manufacture the same product they do), Joe’s employer did not think much about it. Of critical importance, Joe’s employer did not think the new plant would be competing for its most important asset. No doubt the hiring manager at the new plant did plenty of homework, figuring out how much employees at the first company were being paid and offering to pay more. What if the first employer had done some homework, too? They could have worked with the finance department to offer an immediate raise to key employees to retain them and let them know they are highly valued.

3. Perform Preventive Maintenance.

Suppose there was no new plant opening down the road, and Joe was not leaving. What would the schedule for preventive maintenance be? How often should an employer meet with workers? How often should the employer communicate with workers in other ways (newsletters, e-mail, etc.)? How often are employees asked what they think? How often are salaries reviewed? How often do employees have the opportunity to learn new skills?

4. Perform Corrective Maintenance.

No matter how good a supervisor is, sometimes a worker will quit. The key to being a great supervisor is to see this not as a defeat, but as an opportunity. When Joe turned in his notice, his employer could have told him how much he was valued and invited him to come back if the other job does not work out. Taking it a step further, the employer could have put a note on the calendar to call Joe in 3 months and ask how things are going at the new job. At the very least, the employer could keep Joe on the company mailing list and make sure he gets invited to apply the next time an opening becomes available.

The mobility of today’s work force means there always will be workers leaving a company, but it also means there will be workers leaving other companies, too. If employers do not burn bridges, and instead take every opportunity to strengthen those bridges, some workers inevitably will eventually come back across.

Last, But Definitely Not Least

If managing a Generation X work force seems challenging, just wait, because today’s entry-level workers are “Generation Y” (those born after 1980). Generation Y employees may not know anything about insulation, but they understand the law of supply and demand. During their entire lifetimes, demand for workers will far exceed supply. Generation Y is planning to write its own ticket, and modern companies will have to be ready to meet the challenges of an ever-changing work force.