Scaffolding 101: An Introduction

Because scaffolding is ubiquitous, its presence and safety are often taken for granted. As construction-industry professionals, we work on or near scaffolding on a regular basis. We are positioned to manipulate—purposefully or incidentally—scaffold materials. But how much do we know about scaffolding?

According to the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), scaffolding-related violations were ranked third in the list of 2018’s “Top 10 Most Frequently Cited Standards.”1 It is safe to say that most people regularly present on a job site are not scaffold experts. Given the inherent risks, it is important that everyone in proximity have a basic understanding of scaffolding and its accompanying equipment.

When assembled or used incorrectly, scaffolds create serious safety hazards. Last summer, during construction of a major resort in Orlando, Florida, 2 men fell to their deaths when the scaffold they were standing on—nearly 7 floors up—collapsed. Their support structure failed. A third man managed to hang on as the structure gave way beneath him. With the help of several coworkers, he climbed to safety, suffering minor physical injuries.2 The men had been preparing to pour concrete at the time of the incident.

This sobering story illustrates the importance of scaffolding safety. As industry experts, we must maintain an attitude of teachability. Changes and advancements in scaffold materials, regulations, erection, and use necessitate the need for constant and continuous education. This article offers a brief introduction to the diversity and complexity of scaffolding.

Basic Types of Scaffolds

OSHA’s definition of a scaffold includes any “elevated, temporary work platform.”3 The 2 primary types of scaffolding include supported and suspended

- Supported scaffolds are built from the ground up. They include at least 1 platform supported by load-bearing materials such as frames, poles, and legs.

- Suspended scaffolds have at least 1 platform suspended from above using overhead ropes or similar non-rigid material.

The basic types of scaffolds are further delineated into subcategories. For the support scaffold category, here are the types that often appear on a job site:

- Frame scaffolding, which is typically easy to set up and dismantle, and useful in quick up-and-down scenarios, is often used on residential projects.

- Tube and coupler scaffolding is extremely versatile and can be built in multiple directions to suit most situations. Tube and coupler scaffolding takes longer to assemble than frame scaffolding and requires much more experience to build correctly.

- System scaffolding is strong and versatile. It surpasses tube and coupler scaffolding in terms of ease of assembly but takes expertise and training to build.

There are many types of suspended scaffolds, with the most predominant being the 2‑point, adjustable swing stage. You have likely seen these hanging from skyscrapers. They are often used by high-rise window washers. Significant regulation, design criteria, and training are required for this type of scaffolding.

Additionally, other types of equipment (like scissor lifts and aerial lifts) are regarded as scaffolding. Equipment scaffolding is also regulated and requires training. Regardless of subcategory, scaffold material is designed and constructed for 3 types of duty:

- Light duty is capable of withstanding 25 lbs./sq. ft.,

- Medium duty is capable of withstanding 50 lbs./sq. ft., and

- Heavy duty is capable of withstanding 75 lbs./sq. ft.

For the purposes of this article, we will focus on the most commonly encountered type of scaffolding: support scaffolding.

Qualified and Competent Persons

To ensure safety of all workers and clients, scaffolding must be erected by a qualified person. OSHA defines a qualified person as “one who—by possession of a recognized degree, certificate, or professional standing, or who by extensive knowledge, training, and experience—has successfully demonstrated his/her ability to solve or resolve problems related to the subject matter, the work, or the project.”4

Additionally, a competent person must be involved. According to OSHA, a competent person is “one who is capable of identifying existing and predictable hazards in the surroundings or working conditions, which are unsanitary, hazardous to employees, and who has authorization to take prompt corrective measures to eliminate them.”4

It is important to note that having the ability to build a scaffold does not mean the resulting scaffold will be compliant with the qualified and competent designations described above. The drawback to ease of assembly of the simpler scaffolding types, like frame scaffolds, is that a general contractor or subcontractor might erect scaffolding that is noncompliant and potentially hazardous.

Some scaffolding contractors have received teaching accreditation from reputable organizations; and these contractors can provide competent-person training to your employees. The safest course of action, however, is to have a qualified and competent scaffolding contractor provide, build, and maintain the elevated work platform(s). Think of it this way: Would you ask your scaffolding contractor to install cryogenic insulation at your liquid petroleum gas (LPG) plant? Of course not! Insulating LPG equipment is a specialized skill requiring years of training.

Beyond Load Ratings and Assembly

In addition to understanding design types, basic construction, and load ratings of scaffolding, the following details must be considered to create a safe and compliant scaffold platform:

- Guardrail system and toeboards,

- Maximum intended load,

- Personal fall arrest systems (PFAS) and anchorage points, and

- Scaffold inspection and tagging.

Guardrails and Toeboards

Guardrail systems are often a primary reason to construct a scaffold. Naturally, we want workers elevated, but how do we protect them once they are? As a reminder, safety standards require that all scaffold workers elevated at 10 feet or more be protected by some sort of fall protection. Many facilities, clients, or state agencies have an even lower threshold. Therefore, guardrail installation on the work platform is a fundamental reason for scaffolding on site.

Scaffold standards require toprails on supported scaffolds be installed between 38 and 45 inche sabove the platform surface. Toprails must support200 pounds of force. Midrails must be installed at a height midway between the top edge of the guardrail system and the platform surface, and they must support 150 pounds of force. Guardrails must be installed on all edges of the scaffold, with very few (and specific) exceptions—such as working off a leading edge on the surface of a building, where the railing would impede access. Under these exceptional circumstances, other significant fall protection measures must be taken.

Each employee on a scaffold must be provided with protection from falling hand tools, debris, and other small objects. Often, these protections require the use of toeboards. Toeboards are installed along the edge of platforms more than 10 feet above lower levels. They must be a minimum of 3.5 inches tall above decking, have no more than a .25-inch gap between the decking and the toeboard, and must be capable of withstanding 50 pounds of force in any direction.

Maximum Intended Load

Along with duty types (light, medium, and heavy), it is important to consider the maximum intended load for the scaffold.

It is crucial to stay within the scaffold’s load limit. Failure to do so can cause the scaffold to collapse. Just as scaffolds must be designed by a qualified and competent person, they must be built and used as designed, taking into consideration the weight of people, equipment, and additional levels of scaffolding. Any modifications can affect the scaffold’s capacity and stability. Scaffolds and scaffold components must never be loaded in excess of their maximum intended loads or their rated capacities, whichever is less. Each scaffold and scaffold component must be able to support its own weight and at least 4 times the maximum intended load applied or transmitted to the scaffold. (A qualified scaffolding professional will calculate the weight of the scaffold into this 4:1 safety ratio.)

Personal Fall Arrest Systems (PFAS) and Anchorage Points

Can one attach PFAS directly to the scaffold? Under certain conditions, yes; however, it is always recommended that the PFAS be anchored to a structural member capable of supporting the mandated 5,000 pounds per user. The scaffold can be used as an anchorage when the scaffold structure is attached to the building’s structure and all of the following conditions are present:

- The horizontal ties are capable of withstanding a 750-pound lateral pull, with a safety factor of 4:1;

- Ties are installed along the length of the scaffold at intervals not to exceed 30 feet; and

- The scaffold is tied to the structure at the first lift and at intervals not to exceed every 18 feet.

Assuming the scaffold meets the above criteria, where can you actually secure your PFAS? Here are the guidelines concerning anchorage points for systems scaffolds:

- Ledgers of 7 feet or fewer can be used as an anchor point.

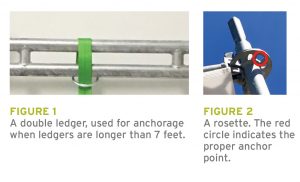

- 10-foot ledgers can be used as an anchor point only if specifically stated in the manufacturer’s specifications. However, if the ledger is greater than 7 feet, the safest course of action is to use double ledgers (see Figure 1).

Rosettes are acceptable anchor points, provided they are attached to the proper (larger) opening (see Figure 2). Again, only anchor PFAS to the scaffold after meeting all the criteria listed.

Scaffold Inspection and Tagging

In accordance with OSHA standards, a competent person must inspect each scaffold and scaffold component for visible defects prior to each work shift and after any occurrence that might affect a scaffold’s structural integrity.4 This inspection is the responsibility of the controlling contractor, unless the job has been subcontracted to a scaffold provider. While inspecting before each work shift might seem excessive, given the life-and-death importance of detecting defects in scaffolds and scaffold components, such frequent inspections are both reasonable and prudent. Scaffold tagging communicates a successful and completed inspection, but these tags are not mandated by OSHA.

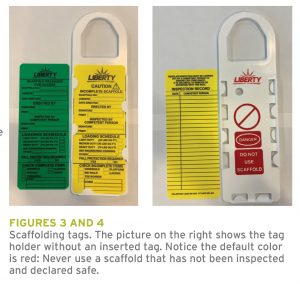

Examples of scaffolding tags appear in Figures 3 and 4.

OSHA does provide guidance regarding specification, design, application, and use of other types of accident-prevention tags, or safety tags. These safety tags are designed to clearly identify a temporary hazard. Safety tags must remain in place until the hazard is eliminated or the hazardous operation completed. The message on the safety tag must clearly convey the potential, type, and degree of hazard that may lead to accidental injury or property damage. Again, these temporary tags are not scaffold inspection tags; if you see these warning tags on a scaffold (or anywhere else), avoid the area and report the issue.

While not mandated or regulated, scaffold inspection tags are generally used by reputable scaffolding contractors. Scaffold inspection tags can vary from site to site, depending on the contractor (or subcontractor). This is as confusing as it sounds—different tagging methods may be present on the same job site if multiple scaffold companies are used. Traditionally, contractors use a color-coded tagging system:

- Green tags indicate a fully compliant scaffold;

- Yellow tags indicate the scaffold is usable, but the inspector has identified hazards (as indicated on the tag); and

- Red tags indicate a hazardous condition that renders the scaffold unsafe has been identified.

In addition, the scaffold tag will often communicate load rating and the name of the competent person, and it will be signed and dated with each inspection. For yellow-tagged scaffolds, deficiencies will be listed (gaps in deck, missing guardrails, fall protection required, etc.). Red tags might be indicated within the tag holder. In these cases, when the yellow or green tag is pulled, the red tag holder states DO NOT USE (Figure 4). Typically, any scaffold with an empty tag holder is designated as a danger. It should not be considered safe until a competent scaffold inspector deems it so. (Note: Not all scaffold companies use an empty tag holder as a warning. Some companies might use red-colored tags.)

For better or worse, because OSHA does not mandate scaffolding tags, not all job sites will have clearly labeled scaffolds.

Conclusion

This crash course in scaffolding provides a sound, high-level view of the basics, but it only scratches the surface of what a conscientious contractor needs to know. Scaffold access and egress, rest platforms, mudsills, ladder placement, self-retractable climbing devices (yo-yos), and much more all need to be addressed on any project that includes scaffolds.

Fortunately, qualified and competent scaffold companies are available nationwide. It is best to verify credentials, investigate incident rates with the Department of Labor, and examine other prequalification standards before you hire a

scaffold contractor.

The risk you and your personnel take with each step onto a scaffold can be managed. A qualified and reputable scaffolding company will help mitigate the risk to your employees, reputation, and bottom line.

Sources:

1. “Top 10 Most Frequently Cited Standards: for Fiscal Year 2018.” U.S. Department of Labor: Occupational Safety and Health Administration, accessed May 28, 2019, www.osha.gov/Top_Ten_Standards.html.

2. Stanglin, Doug. “2 Die in Scaffolding Collapse Near Disney World in Orlando; 3rd Hangs on and Climbs to Safety,” Florida Today, August 29, 2018, www.floridatoday.com/story/news/2018/08/29/construction-workers-die-scaffolding-collapse-disney-orlando/1130865002.

3. “Scaffolding eTools.” U.S. Department of Labor: Occupational Safety and Health Administration, accessed May 28, 2019, www.osha.gov/SLTC/etools/scaffolding/index.html.

4. “A Guide to Scaffold Use in the Construction Industry: OSHA 3150.” U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 2002 (Revised), www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3150/osha3150.html.

Copyright 2019 National Insulation Association. All rights reserved.