The Fall of the Oil Age?

You may not like my premises for this article, listed below. Some may think I’m being overly pessimistic about world oil prices and its effect. Others will think I’m being overly optimistic about the mechanical insulation industry’s future. All I can say is, "To each his own."

-

The world and the American economies are heavily dependent on prices of crude oil and other non-renewable fuel sources.

-

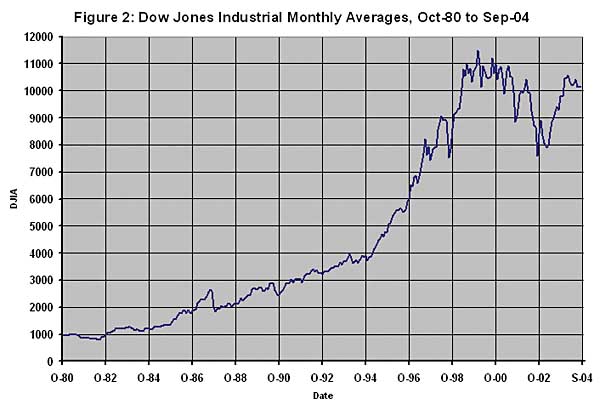

The U.S. stock market during the past 30-plus years has responded positively to reducing crude oil prices and negatively to increasing prices.

-

World and American consumption of crude oil, at the current rate of increase, is unsustainable.

-

Crude oil production will reach a peak, after which it will decrease.

-

After the peak in crude oil production, the world and the American economies will respond with reduced demand until demand equals supply.

-

The mechanical insulation industry, and other energy-conserving and energy-reducing technologies, will enjoy a renaissance of increased business.

-

Now is the time to prepare for the future.

-

To prepare for the future, we can look at lessons learned during the 1979-1983"energy crisis."

The Impact of Crude Oil on the U.S. Economy

The story of oil exploration and oil use, as we know it today, really began in 1859, a couple of years before the start of the American Civil War. Edwin L. Drake, a former railroad conductor, drilled the first oil well in Titusville, in northwestern Pennsylvania, in an area rich with oil seepage. It was soon discovered that this oil could be used in lamps to replace the use of whale oil, a timely discovery since whales were being killed off to near-extinction.

Two years later, in Germany, Nikolaus Otto invented the first gasoline-burning engine. The oil age had begun! Of course, no one here in America really noticed since we Americans were too busy fighting each other over whether we were going to be one nation or two, and whether we would continue the institution of slavery. But when the Civil War was over, American economic growth took off and continued for 145 years to the present, although disrupted by numerous financial panics such as those in 1873 and in 1929, each followed by a depression.

Although other people discovered oil fields in the United States in the years following the Civil War, the discovery rate really took off in the 20th century. Some of those fields are still providing oil today, some 60 to 80 years later. But, oil field discovery peaked in the 1930s and declined after that. The rate of U.S. oil field discovery has never again come close to the success it had in the 1930s.

One major reason for American growth since the Civil War was our abundance of natural resources. These included land, wood, numerous minerals, fresh water and of course,

ossil fuels: coal, natural gas and crude oil. Wood and coal largely fueled our growth from the Civil War to the early part of the 20th century. However, the advent of the automobile age really started with Ford Motor’s launch of the first mass-produced car, the Model ‘T’ in 1908, leading domestically produced oil to became a critical component of the American economy. When I was born in 1948, domestic oil production was sufficient to meet demand, with little need for imported oil. Few people in American public life worried then about future supplies of crude oil. There seemed to be enough oil to last the United States forever.

Following World War II, America grew economically through the late 1940s, ’50s and into the ’60s as the undisputed economic leader of the world, fueled to a large extent by our huge reserves of fossil fuel and in particular of crude oil. Of course, that is a position that we hold today.

Once we started to import significant quantities of crude oil during the 1960s, we became susceptible to supply disruptions. First, there were supply disruptions in 1973 following the Yom Kippur War, when the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) first became a household word by "flexing their muscles." Also, there was a major disruption in 1979 following the Iranian Revolution when OPEC reduced its quota, causing world oil prices to increase dramatically. This event was followed in 1980 by the Iran-Iraq War, which resulted in oil tankers being sunk in the Straits of Hormuz, temporarily blocking ships and cutting off oil shipments from the Persian Gulf.

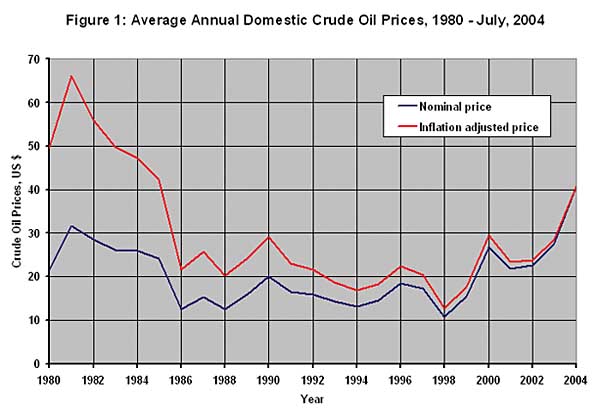

Crude oil prices spiked to more than $80 per barrel in 1980 (in 2004 dollars), only to drop steadily after that to less than $20 by mid-1988. The primary reason for this price collapse was that OPEC had basically overpriced its oil, which resulted in severe damage to the world economy, and hence resulted in a precipitous drop in oil demand. With oil prices steadily dropping after 1980, and natural gas prices dropping as well, the badly crippled U.S. economy came roaring back in 1983, flush with cheaper energy and a new optimism. As many of us remember, rapid American economic growth also soon pulled up the other industrialized, capitalistic countries.

It is important to understand that this 1979-1982 "energy crisis" was caused primarily by OPEC’s restrictions on production output and by supply disruptions, not by a sudden increase in demand that exceeded production capacity. In fact, during those years, world demand actually dropped significantly due to Americans and others taking energy conservation, energy efficiency and use of alternative energy sources seriously in several ways: insulating their uninsulated older homes, adding wood-burning stoves to their houses, replacing their old "gas guzzler" automobiles with smaller, fuel-efficient ones, adding more efficient furnaces and air conditioners, using programmable thermostats and numerous other steps.

There was a flurry of interest in the United States to design and build solar-heated houses. You may have heard the story about a dairy farmer who put plastic sheeting over his manure pile so as to collect the methane gas emitted by the composting manure, then heated his house and ran his farm with this gas.

There were numerous other such stories. Many building codes that affected building energy use were revised to require more insulation, use of reflective glass, installation of more efficient mechanical equipment and reduced ventilation rates, to name a few changes. Industry started using greater thicknesses of mechanical insulation and paid more attention to its consumption of precious electricity, natural gas and oil products. There was a construction wave of both coal-fired and nuclear-powered electrical generating stations, all of which required huge quantities of mechanical insulation. As an American society, we haven’t seen so many energy- and insulation-related innovations and investments in the more than two decades since.

By 1986, however, energy conservation in the United States had become passé. By then, it was too easy to make money on Wall Street, in real estate speculation and in other types of business. The stock market, which dropped to as low as 800 in 1982, exploded afterwards, reaching the 2700 level by early October 1987, before "the bubble burst." With a new real estate boom, big houses became fashionable, soon to be followed by big cars. By 1986, oil had hit a low of $10 per barrel at one point, and no one was worried about limits to world oil capacity.

As most of us remember, there were anxieties in the oil markets about oil supplies after Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, prior to the United States and others driving the Iraqi army out of Kuwait in early 1991. Oil jumped up briefly to $30 per barrel shortly after the invasion of Kuwait, but after Saddam Hussein’s military forces were either destroyed or sent scurrying back to Iraq, the price dropped to around $16. During most of the remainder of the 1990s, oil prices remained low in the $10 to $20 range, and the U.S. economy grew at a spectacular rate. Furthermore, the U.S. stock market again went through explosive growth of 20 percent or more per year on average, with the Dow Jones industrial average more than tripling from about 3,600 in early 1993, to a high of about 11,500 in early 2000, when the technology bubble finally burst.

It is memorable that the relatively recent low energy prices occurred early in 1998 when world crude oil prices hit a low of $10 per barrel, further boosting the stock market, real estate and other investor assets. Cheap energy was abundant. Hundreds of thousands of Americans traded in their small and mid-sized sedans, which averaged more than 25 miles per gallon, for large vehicles weighing more than 6,000 pounds and averaging 10 to 15 miles per gallon in fuel economy.

Likewise, new houses continued to be built increasingly larger, requiring more energy to heat and cool (the average new house size today is more than double that of new houses built in 1972). And, these houses continued to be built in rapidly expanding suburbs (like my town of Fishers, Indiana) further removed from the city centers, such as Indianapolis, requiring people to drive greater distances for more hours on increasingly congested highways, thereby consuming increasing amounts of petroleum-based fuel.

Finally, in late 1999, OPEC got its act together and curbed its rate of production. World oil prices subsequently rose, reaching $35 a barrel at one point during the summer of 2000, about three times the price of a few years earlier. In March 2000, the overly exuberant U.S. stock market finally peaked at 11,500 as oil prices continued to rise. The financial bull market was over, and the boom economy of the 1990s came to an end. The stock market settled down to around 10,500 more than four years ago and, as of press time, is about a hundred points below that. However, Americans’ preference for low-mileage vehicles, larger houses and driving longer distances not only has not altered but also has in fact continued to increase. And yet, at the time of writing this article, oil sells for about $50 per barrel. The public apparently believes these high crude oil prices are temporary and that crude oil supplies will last forever. See Figures 1 and 2.

Hubbert’s Curve and the Oil Age

In the 1950s there was a geophysicist working for Shell Oil in Houston named M. King Hubbert, Ph.D. Born in 1902, he received his doctorate from the University of Chicago in the ’20s and then tried teaching in college. However, he became quickly disillusioned by university life and changed careers by taking a job with an oil company in his native Texas.

Using geology, physics and mathematical statistical modeling, Dr. Hubbert developed a model for predicting the life expectancy of an oil field, from the time oil is first extracted, to the time it reaches maximum production, to the time it runs dry. He did something more original, however, in applying that mathematical model to all U.S. oil fields, as if they collectively made up one large field. In so doing, in 1949, when crude oil sold for about $2.50 per barrel, he predicted that the duration of an oil age should be, and would be, short lived, relative to the age of civilization, and would eventually come to an end. Then in 1956, he shocked his colleagues when he predicted that U.S. oil production would peak in 1970, using a statistical distribution curve. Regardless of pressure from his management and colleagues not to publicize his theory, he did so. Many of his colleagues immediately condemned his theory.

However, 14 years later, in 1970, U.S. oil production did actually peak, as Dr. Hubbert had predicted, at about 9.5 million barrels per day (MBD). No one in the oil extraction business criticized him any longer. He had their undivided attention. Dr. Hubbert died of natural causes in 1989 but had predicted the end of the oil age for planet Earth would come within a few decades, not within a few millennia or

centuries.

Unfortunately, few Americans noticed or cared that U.S. oil production had peaked. We were already consuming more oil per year than our fields could produce; so we simply imported increasing quantities of $3.18-per-barrel oil from other countries. It was simply no big deal to do so: The politicians didn’t care; the auto industry didn’t care; investors didn’t care, and the general public didn’t care. Furthermore, no one knew or much cared what the recently formed organization OPEC did or stood for.

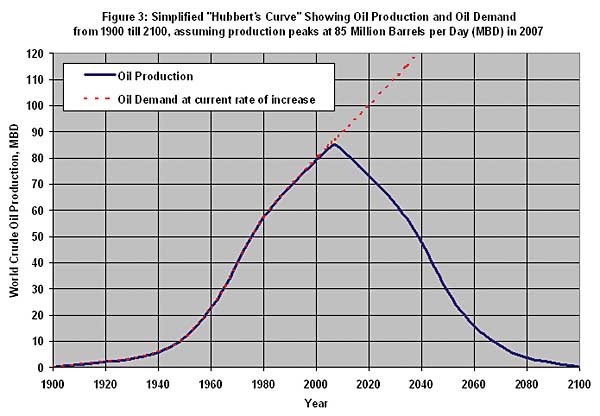

Later, Dr. Hubbert applied the same methodology and developed curve for the entire Earth, treating the Earth as if it originally started with one huge 2 trillion barrel oil field, the total amount of oil that many geologists estimate the world had in 1859. In so doing, he developed what now referred to as "Hubbert’s Curve." While there is some uncertainty, as there is with any statistical models, oil experts now agree that a peak in world oil production will occur sooner or later. Many agree that this peak will occur as early as 2007 and perhaps as late as 2010, when they estimate we will have consumed about 1 trillion barrels of oil, or about half of the 2 trillion barrels originally present in the earth. That’s as little as three years from now, leaving mankind only 1 trillion barrels for the rest of time.

While there is a lot of debate about the shape of Hubbert’s Curve, the 2 trillion barrel quantity and the peaking of world oil production within this decade, there is no debate about the basic concept: There is some finite quantity of crude oil, and at some point, with demand increasing year after year, the peak will be reached. And, when the peak is reached and demand exceeds supply, oil economics will change dramatically, whether it occurs in three years or 30.

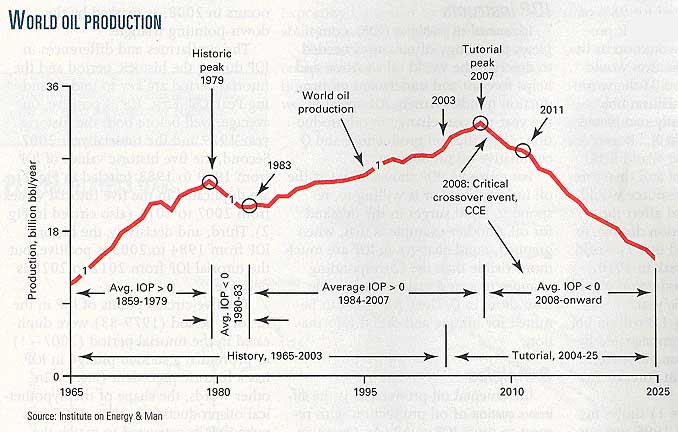

Figure 3 shows a simplified version of Hubbert’s Curve, which explains the peak concept and compares it to increasing demand. Figure 4 shows simplified record of world oil consumption since 1950 with projections of consumption until 2050.

A number of people are highly critical of Hubbert’s Curve and the whole peak concept because they say it is overly apocalyptic and doesn’t account for new technology that allows, for example, oil companies to extract oil from off-shore, deep water wells or from oil shale and oil sands. Some of this technology didn’t exist 20 years ago, and Dr. Hubbert certainly didn’t know about it. Figure 5 accounts for these changes and shows the shift that might occur with an additional 1.3 trillion barrels of oil, added to the 1 trillion in reserves that we already know about, for a total of 2.3 trillion barrels left for our future. As expected, this graph shows that, due to the rapid increase in our consumption, the peak would indeed be shifted. Surprisingly, even with 1.3 trillion additional barrels of oil discovered, the peak would be shifted by only three years!

Today, the world is using between 82 and 83 MBD, with the United States using about one-fourth of that total, or about 20.5 MBD. That’s the equivalent of about 3 gallons per day for every American: man, woman and child! China, India, Pakistan and other Asian countries have continued spectacular economic growth, leading to large increases in their oil consumption of this non-renewable resource. In fact, China, with its 1.3 billion people, has recently surpassed Japan to become the second largest oil consumer in the world, using about 6 MBD, with this increasing at almost 10 percent per year. Overall, there is no end in sight for that demand growth, short of what will happen when the price increases to new levels. And as this goes on, some geologists, using Hubbert’s Curve, predict that the peak in his curve will occur when demand reaches about 85 MBD. And this, they say, could occur less than three years from now in the year 2007.

The principle here is simple: The peak will occur when we’ve used half of the crude oil ever placed in the Earth. When we get to that halfway point, the rate of oil extraction will no longer be capable of keeping pace with the growing demand for oil. So, demand will exceed supply. OPEC countries will no longer have any spare capacity to increase production. They will be at full production. When demand exceeds supply, one thing always happens: The price rises until demand and supply are again equal. That’s economics 101. And, the greater the gap between demand and supply, the greater the rise in price.

The authors of the book, "The Oil Factor," Stephen and Donna Leeb, predict $100-per-barrel oil by the end of this decade and $10-per-gallon gasoline at the pump. While that may be overly apocalyptic, it is my opinion that crude oil prices will be much higher than they are today. As I write this article in late September 2004, oil futures have stubbornly held above $40 per barrel for several months in spite of predictions that they would tumble after Labor Day to the $35 price range. At the end of September, oil futures exceeded $50 for a day.

These prices just aren’t showing any inclination to drop very much, and world disruptions, such as Hurricane Ivan, attacks on oil pipelines in the Middle East, production cuts due to political issues by the Russian oil giant Yukos, political unrest in Venezuela, and ethnic warfare in Nigeria, simply make the supply problems worse and result in further oil price increases. However, these disruptions are likely only temporary issues that obscure the root cause of the problem. This coming "energy crisis," currently in its infancy in my opinion, is primarily being caused by surging world oil demand rather than by oil supply problems. When we reach the peak in world oil production, higher oil prices are inevitable until demand is curtailed and brought back into line with world production capabilities. Anyone can guess at how high oil prices and gasoline prices will rise, but one thing is certain to me and to many others: By the end of the decade, we will look back fondly at 2004 and its unbelievably cheap oil.

What Are the Solutions to High Crude Oil Prices?

We saw in the last "energy crisis" of a quarter century ago how the world can respond to higher energy prices. Today, due to higher oil prices, there is a greater rate of oil drilling here in the United States than in many years, as well as drilling for natural gas. There is much speculation among energy experts about increasing the production of the profitable oil sands project in Canada and of increasing production on the oil shale and sands projects in northwestern Colorado and northeastern Utah. Today, they produce about 1 MBD, or almost 5 percent of the U.S. total consumption, and are expected to increase to 2 MBD within 10 years.

There are almost 100 new coal-fired electric power plants in some part of the permitting-design-construction process to take advantage of America’s huge resources of relatively cheap coal. And, some eight electric utilities are talking about building new nuclear power plants, the first such talk in more than a quarter of a century, to take advantage of relatively cheap nuclear fuel. There are also a number of liquefied natural gas (LNG)-receiving terminals in some part of the permitting-design-construction process to allow importation of natural gas. In fact, LNG imports have increased by more than 50 percent to the United States in the past year. Natural gas production peaked in the United States a couple of years ago, but there are huge reserves in Russia and Iran waiting to be tapped after LNG liquefaction facilities are constructed. There is an increasing demand for hybrid automobiles, reportedly requiring over a year for delivery. All of these changes are driven by economics, with the key economic ingredient being expensive crude oil and natural gas.

What Do Increasing Crude Oil Prices Mean for the Mechanical Insulation Industry’s Future?

No one would argue that a continuing increase in the cost of non-renewable fossil fuels is potentially disruptive to both the United States and the overall world economies, the stock market and the economic confidence of consumers, and business. However, just as during the "energy crisis" of 1979-1983, there are certain businesses that will do extremely well. Obviously those businesses that own large fossil fuel reserves will do well, as will fossil fuel exploration companies. In addition, however, companies in the energy conservation business should do very well. One of those is the mechanical insulation business.

I started in the mechanical insulation industry 26 years ago when our country, and the world, was still reacting to the 1973 "energy crisis." I started my career in 1978 at an industrial research center for a major insulation manufacturer. At the time, the company grew rapidly, at about 100 people per year, and there were numerous exciting and well-funded projects associated with energy conservation. The laboratory group where I worked in those days couldn’t spend all the money we were allocated in those years. In addition, soon after I arrived, I was also trained to go back to Purdue University, where I had received my master’s degree, to recruit more graduate students since there was such a huge demand for these technically trained people and there was money to pay for them. After all, I was working for a large insulation manufacturer and business was great.

At professional organizations, such as ASHRAE, there was much excitement and activity on a solar energy technical committee (I believe it was called). Elsewhere, there were numerous conferences on such topics as thermal envelope performance, natural day lighting of buildings and heat pump efficiency, all very well attended. These conditions were to continue until about 1984, all during a time of extremely high energy prices.

Then, seemingly without warning, it all came to an abrupt end and economic reality returned to those of us in the insulation industry. Energy prices dropped; the energy conservation economy came to a screeching halt, and the industrial research center where I worked started laying people off, while other portions of the U.S. economy grew rapidly. Although insulation contractors continued to have plenty of work for several years afterwards, due to a large backlog of coal and nuclear power plant construction and a large backlog of fly-ash removal system installations on existing coal-fired plants, the mechanical insulation industry hasn’t seen a period of such growth and prosperity since that time.

Also, during these earlier "energy crises," most energy-conserving and energy-efficiency technologies received much attention from the public, industry and government. Furthermore, consumers and businesses were willing to pay for the benefits of these technologies. Mechanical insulation was one of those technologies that received a great deal of that attention and one that became highly appreciated, perhaps more than it ever had. This can happen again; in fact, with effective publicity about the benefits of mechanical insulation, it can happen more so than before. This is because mechanical insulation is simply the most cost-effective means of conserving thermal energy.

Let me give you an example to illustrate the cost effectiveness of mechanical insulation. Using results from a Department of Energy publication, "Industrial Insulation for Systems Operating above Ambient Temperature," a flat, vertical, 600 F surface was determined to have an economic thickness of 4 inches of insulation, based on energy costing $6/MMBtu, and that insulation will reduce heat loss by 18.8 MMBtu/ft2 per year. Since one barrel of oil contains about 6 MMBtu of energy, that means each square foot of this insulation system saves a little more than three barrels of oil per year. Take that to the bank! Figure 6 shows how many barrels of oil equivalent can be saved for each year of service of this insulation.

In one year, then, if we assume that a 4-inch-thick, metal lagged panel insulation system costs $20 per ft2 installed and the oil cost $36 per barrel (which is equivalent to about $6/MMBtu), the insulation system would pay for itself, or have a payback of more than five times in that one year. (Payback = $36 / barrel x (18.8 MMBtu / ft2 per year / 6 MMBtu / barrel) / $20 / ft2 installed cost.) At a cost of $50 per barrel of oil, it would pay for itself eight times each year! Mechanical insulation is simply the most cost-effective way of saving thermal energy. It’s about time the public came to realize its cost-effectiveness.

Unfortunately, mechanical insulation is not widely appreciated for its cost-effectiveness in saving thermal energy. We all have to wonder: How cost-effective does mechanical insulation have to become to be appreciated? Or, maybe the correct question is, "How expensive do crude oil and natural gas have to get before people appreciate the energy-saving benefits of mechanical insulation?" I am confident that the time is ripe for our products and services to be highly appreciated for their thermal energy savings.

I further predict that those of us in the mechanical insulation industry will soon be in the driver’s seat: We will be asked to educate our customers, and educate society in general, of the effectiveness of our products and services in conserving thermal energy. By taking NIA’s Energy Appraisal Program, and maintaining expertise in running the computer program 3E Plus®, people in the mechanical insulation business can, in my opinion, make our industry grow at least 10 percent per year, from now on, up to the time of Hubbert’s Peak in world oil production, and more than 10 percent per year afterward.

Conclusion

So, will the next few years, as we approach the peak in world oil production, be good or bad for us? It should be a healthy change for the mechanical insulation industry, assuming that we are prepared and proactive. Our products and services will become more valuable, and subsequently in greater demand, allowing for higher prices than allowed before. Consequently, investments in companies that provide mechanical insulation products and services should fare much better than they have for many years, as will other energy-saving technologies. Likewise, of course, companies in the oil, natural gas and coal business will continue to be very profitable, as many investors have already recognized.

It will be an opportunity for those of us in this industry to serve our customers with pride and dignity as our industry will finally have the chance to be recognized for the value of our energy-saving products and services. By being well-run and always promoting our products and services, NIA member companies, and our industry, should sustain healthy and steady growth for many years into the future.

For a few good stock tips, if you know of a company in the mechanical insulation industry that is well-run and future-oriented, I would recommend that you invest in it. I’ll bet you that during the next decade, it will do a whole lot better than the Dow Jones Industrial Average!