National Association of State Energy Offices (NASEO) Publishes New Report on Energy Efficient and Healthy K-12 Public Schools

NASEO released a new publication, Energy Efficient and Healthy K-12 Public School Facilities: Opportunities for State Energy Offices and State Education Agencies to Collaborate (Report), detailing how State and Territory Energy Offices and their state agency partners can play an important role in supporting sustainable, energy efficient, and healthy K–12 public school facilities.

For State and Territory Energy Offices, school energy programs can be an opportunity to support multiple goals: workforce development, helping communities manage their energy costs, supporting community resilience, increasing student and teacher energy literacy, and meeting statewide energy and emission reduction targets for buildings. The Report presents opportunities and recommendations for State and Territory Energy Offices to collaborate with State Education Agencies to help local school districts with:

- Stakeholder engagement and decision-making,

- Energy data management,

- Facility design and planning,

- Access to funding and financing,

- Technical assistance for facilities management staff, and

- Compliance with codes and standards.

The Report mentioned installing insulation three times (emphasis added in the following text for Insulation Outlook readers) as a technology that should be prioritized to help reduce energy and help free up money for the schools.

On page 8 of the Report, it states,

State Education Agencies and local districts may not prioritize energy savings measures or energy efficiency improvements because energy is a relatively small budget item and is treated as a “fixed cost.” Reducing energy expenditures, however, can free up crucial funds for other budget requirements and be used to address annual facilities funding gaps. To support local education agencies (LEAs) in conducting facility energy improvements, some State Energy Offices provide lists of approved energy service providers and contractors, template solicitation and contract documents, and other resources.1 Through these offerings, states can facilitate Energy Savings Performance Contracting (ESPC) for LEAs, which are typically offered through energy service providers to allow budget-neutral building improvements that require no up-front costs and are instead paid back through incremental energy cost savings. ESPC projects may include purchasing and

installing new high-efficiency HVAC systems, insulation improvements, window replacements, LED lighting installations, and more. Using ESPCs, LEAs can make facility improvements that help improve occupant health, such as optimizing thermal comfort with adequate heating and air-conditioning systems, replacing outdated and poor-performing HVAC systems, and introducing smart controls for energy and indoor air quality systems. LEAs can also reinvest savings in other areas, including capital improvements to meet various health and safety needs, hiring and retaining teachers, and supporting the schools’ educational mission.

Further insights on page 10 noted,

While the nation’s elementary and secondary public school districts vary in enrollment size, geography, demographics, and access to capital from tax revenue, bond authority, and other sources of funding, they share many of the same types of facilities challenges. School districts with economically disadvantaged students making up 65% or more of their student population (“high poverty” school districts) spent 37% less per school on capital investments over a 10-year period than school districts with economically disadvantaged tudents making up less than 33% of theirstudent population (“low poverty” school districts).4 According to a 2020 U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report describing the needs of K–12 public schools nationally, about half of the schools visited required HVAC system updates, with aged and leaking equipment damaging flooring and ceiling tiles and leading to mold and indoor air quality problems.5 Chronic underinvestment in required capital projects due to budget constraints and the need to meet high operating costs are resulting in accumulated building deficiencies that negatively affect occupant health, safety, and educational attainment.

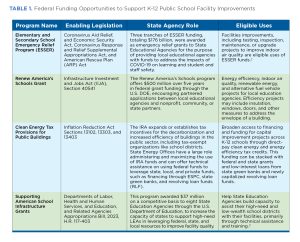

Using expanded tax incentives under the Inflation Reduction Act allowing direct pay for

local governments, such as the 48E investment tax credit, the 45W commercial clean vehicle tax credit, and the 179D tax deduction for energy efficient commercial buildings (alone or in combination with grants and financing mechanisms like ESPC to conduct low-cost retrofit projects with short to medium [5–15 year] payback periods), LEAs can free up funding from annual operations budgets through energy cost savings. Low-cost retrofit projects may include envelope upgrades, efficient lighting installations, and insulation improvements. By packaging energy efficiency measures that reduce operational energy costs with mechanical ventilation measures for improved indoor air quality or AC to address extreme heat, LEAs can more reliably anticipate investments to generate positive returns or, at the very least, break even over the lifetime of the equipment upgrade. LEAs can utilize subsequent budget savings and state-supported financing solutions to implement combined renewable energy and energy efficiency projects that shield districts from future energy cost volatility.6 Increasing efficiency at K–12 school buildings mitigates unnecessary energy costs, frees up funding for other crucial school district uses, and provides pathways for schools to manage future energy costs.

Resources:

1. One such example is the Energy Savings Performance Contracts program through the New Mexico Energy Conservation and Management Division, New Mexico’s State Energy Office. The agency maintains state price agreements with nine energy service companies.

Since 2013, the State Energy Office has approved 35 projects, including four in K–12 schools. These projects have resulted in more than $11.5 million in annual savings and reduced energy consumption by an average of 31.9% per project. New Mexico Energy Conservation and Management Division, Energy Savings Performance Contracts. New Mexico Energy, Minerals, and Natural Resources Department (www.emnrd.nm.gov/ecmd).

2. U.S. Department of Education (December 2022) Frequently Asked Questions: Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Programs, Governor’s Emergency Education Relief Programs (www.ed.gov/sites/ed/files/2022/12/ESSER-and-GEER-Use-of-Funds-FAQs-December-7-2022-Update-1.pdf).

3. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary & Secondary Education Supporting America’s School Infrastructure Grant Program (SASI) (www.ed.gov/grants-and-programs/grants-birth-grade-12/school-infrastructure-programs/supporting-americas-school-infrastructure-grant-program-sasi).

4. Filardo, Mary (2021). 2021 State of Our Schools: America’s PK–12 Public School Facilities 2021. 21st Century School Fund (www. Facilitiescouncil.org/s/SOOS-IWBI2021-2_21CSF-print_final.pdf).

5. U.S. General Accounting Office. (2020). K–12 Education: School Districts Frequently Identified Multiple Building Systems Needing Updates or Replacement. (GAO-20-494). United States Government Accountability Office (www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-494.pdf).

6. Torcellini, P., Zaleski, S., McIntyre, M. NREL. (2021). Affordable Zero Energy K–12 Schools: The Cost Barrier Illusion. (https://betterbuildingssolutioncenter.energy.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/80766.pdf).