Cause and Effect: Condensation Control and Mold Prevention

Air contains water vapor. Water vapor originates from our environment—rain and evaporation from open water, groundwater, etc. The amount of water vapor that air can hold is dependent on the air temperature (ambient temperature). As the temperature rises, air can retain higher levels of water vapor.

Relative humidity (RH) refers to the percentage of water vapor present in the air at a specific temperature compared to the maximum amount of water vapor that the air could hold at the same temperature. RH is referenced as a percentage (current/maximum).

Dew point is defined as the air temperature at which water vapor in the air condenses into liquid form. Dew point indicates how much moisture is present in the air and determines RH. For example, an air temperature of 70°F at 35% RH equals a dew point of 41.1°F. At the same temperature with RH at 60%, the dew point increases to 55.5% RH. The outer surfaces of insulation must be maintained above the dew point to prevent condensation.

Air with higher levels of moisture will migrate to areas of lower moisture content. Once air becomes saturated with water vapor, water vapor will migrate to air with lower concentrations of water vapor. When water vapor migrates to a cold surface, it loses energy and condenses. Condensation occurs when humidified air contacts a surface that is below the dew point temperature.

The reality is that building mechanical systems—such as HVAC/R and plumbing piping, equipment, and ductwork—are susceptible to the effects of the trio of ambient temperature, RH, and dew point. Since water vapor will always be present within the building envelope, it is imperative to adequately protect building mechanical systems from its undesirable effects. Left unchecked, uncontrolled water vapor can create a domino effect: vapor drive, condensation, decreased energy efficiency, and the potential for mold growth, corrosion, damage to expensive equipment and building components, slip/fall hazards, and eventual system failure/shut down.

Mechanical insulation is a proven and effective solution that addresses the trio mentioned above (ambient temperature, RH, and dew point). There are many commercially available insulation products and accessories that provide system protection. Due to the variety of mechanical systems and their operating requirements, it is common for multiple insulation types and accessories to be specified and installed on a single project.

Each insulation application is always a system, regardless of its size and complexity. At a basic level, there will always be a substrate, insulation, and vapor barrier (dependent upon the application). Additional insulation components could include adhesives, fasteners, tapes, sealants, and coatings. These systems can become more complex with the addition of insulation layers, fittings, valves, flanges, vapor stops, expansion/contraction joints, slip joints, and other system components.

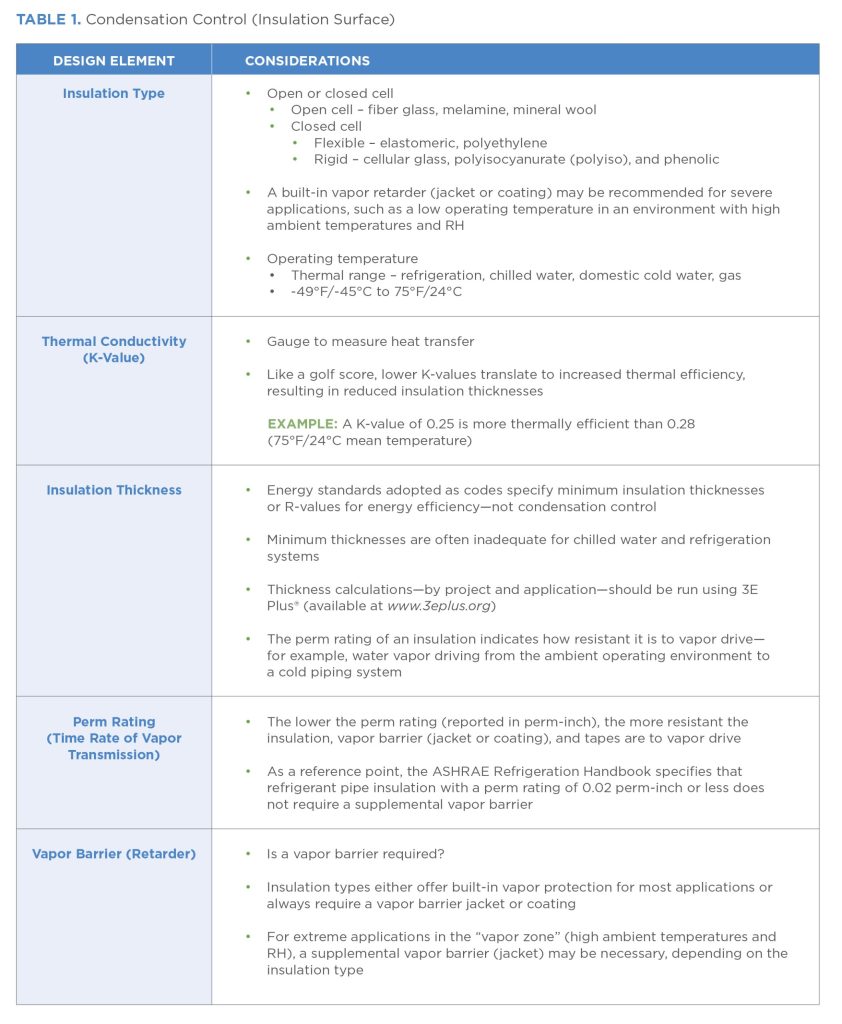

Design Considerations for Below-Ambient Systems

Let’s dive into the design considerations for mechanical insulation to confidently prevent condensation and mold growth on systems that operate at below-ambient (cold) temperatures with an insulation system. Table 1 provides an overview of design elements and considerations for such systems.

Mold Prevention

Mold and condensation are intertwined. Without a water source (condensation), microbes cannot survive on organic food sources alone. When condensation is effectively controlled, mold prevention is achieved.

Like water vapor, it’s not a matter of if, but when mold spores enter a building through openings such as windows and doors, pipe penetrations, open seams in the building envelope, outdoor air intakes, and roof leakage. Additionally, mold typically grows at ambient temperatures ranging from 40°F/4°C to 100°F/38°C with RH above 55%.

With a source of food and moisture, mold spores can grow on any surface, including impervious objects such as glass, metal, and tile. Limited or uncontrolled mold growth in buildings poses a significant liability and real costs to building owners, so it is critical to factor a mold-resistant insulation strategy into building mechanical systems during the design stage.

Because mold spores can digest most organic matter, moisture control is the determining factor, since they cannot live without water. Sources of moisture in buildings include roof leaks, condensation on building mechanical systems, pipe leaks, deferred maintenance, malfunctioning humidification systems, and uncontrolled humidity, to name a few.

Since mechanical insulation is often installed in areas that are not easily accessible for maintenance, insulation material selection is critical. It may be next to impossible to keep organic food sources such as drywall dust, dust, and dirt off the insulation surface, but controlling condensation can be achieved with the proper insulation type, thickness, and vapor barrier (if required).

Insulation and accessory manufacturers report compliance with ASTM and UL standards for mold growth and mildew resistance. Insulations can be naturally microbial-resistant, meaning that the insulation does not contain any food sources such as oils, binders, and resins within and on the insulation surface. Other insulations are available with added EPA registered antimicrobial protection, published in manufacturer technical data sheets and websites.

Sources

- “Moisture Control and Insulation Systems in Buildings, Chilled Water Pipes and Underground Pipes,” William Allen Lotz, P.E.

- National Weather Service, www.weather.gov/arx/why_dewpoint_vs_humidity

- ASHRAE Refrigeration Handbook, www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/ashrae-handbook/2022-ashrae-handbook-refrigeration

- ASHRAE 90.1, www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/bookstore/standard-90-1

- International Energy Conservation Code®, https://codes.iccsafe.org/content/IECC2024V1.0

- Insulation Outlook, www.insulation.org/io/articles/mold-mildew-and-insulation

- 3E Plus, www.3eplus.org

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/epas-registered-antimicrobial-products-effective-sterilants-list