Hourly Fire Ratings—What’s the Deal?

When it comes to mechanical and industrial insulation materials, one of the most commonly asked questions is: “What’s the hourly fire rating of this material?” While the question may seem straightforward, the answer is anything but simple. Understanding fire ratings especially those based on ASTM E119 Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Building Construction and Materials, or UL 263 Standard for Safety of Fire Tests of Building Construction Materials—requires a deeper look into the intended application, the design requirements, and the specific fire testing standards involved.

In the world of mechanical and industrial insulation, we frequently encounter references to various fire-related standards. These include:

- ASTM E84 / UL 723–Flame spread and smoke development

- ASTM E136 / ISO 1182–Combustibility

- ASTM E119 / UL 263 and ASTM E1529 / UL 1709–Hourly fire ratings

While these standards are interconnected in the broader context of fire safety, they serve distinct purposes and should not be confused with one another. For example, a product performing well in flame spread and smoke development tests does not necessarily mean that it is noncombustible or capable of achieving an hourly fire rating.

This article breaks down these concepts to better understand how they relate to insulation systems and fire safety.

Understanding the Different Fire Tests

Flame Spread and Smoke Development (ASTM E84 / UL 723)

These tests measure how quickly flames travel across the surface of a material and how much smoke is produced during combustion. The results are typically expressed as numerical values, with lower numbers indicating better performance. Materials with

low flame spread and smoke development ratings, such as a flame spread of 25 or lower and a smoke development of 50 or lower, are often approved for exposed applications, such as in plenum spaces.

However, these ratings do not indicate whether a material is noncombustible, or how long it can withstand fire exposure. They simply tell us how the material behaves in the early stages of a fire.

Combustibility (ASTM E136 / ISO 1182)

Combustibility tests determine whether a material contributes fuel to a fire. A noncombustible material will not ignite or release significant heat when exposed to fire. This is critical for applications where fire containment is essential, such as in fire-rated wall assemblies, or around structural steel.

Combustibility is often misunderstood. Just because a material has a low flame spread rating doesn’t mean it’s noncombustible. Combustibility tests are more stringent and focus on the material’s ability to resist ignition and heat release.

Hourly Fire Ratings (ASTM E119 / UL 263 and ASTM E1529 / UL 1709)

Hourly fire ratings are perhaps the most complex and misunderstood of all fire-related standards. These ratings are not assigned to individual materials but to systems—assemblies of materials designed to work together to resist fire for a specified period.

ASTM E119 and its UL counterpart, UL 263, are the standard test methods used to evaluate the fire resistance of building constructions and materials. They apply to wall partitions, structural elements (beams and columns), and piping systems in applications such as commercial buildings. The goal is to determine how long a system can contain a fire or resist heat ingress before failing.

ASTM E119 and UL 263 use the same test procedure, but the UL test method is used for UL listed assemblies that identify specific assembly components, such as the manufacturer of the partition elements, and product names rather than general material descriptions like “type X gypsum” and “mineral fiber insulation.”

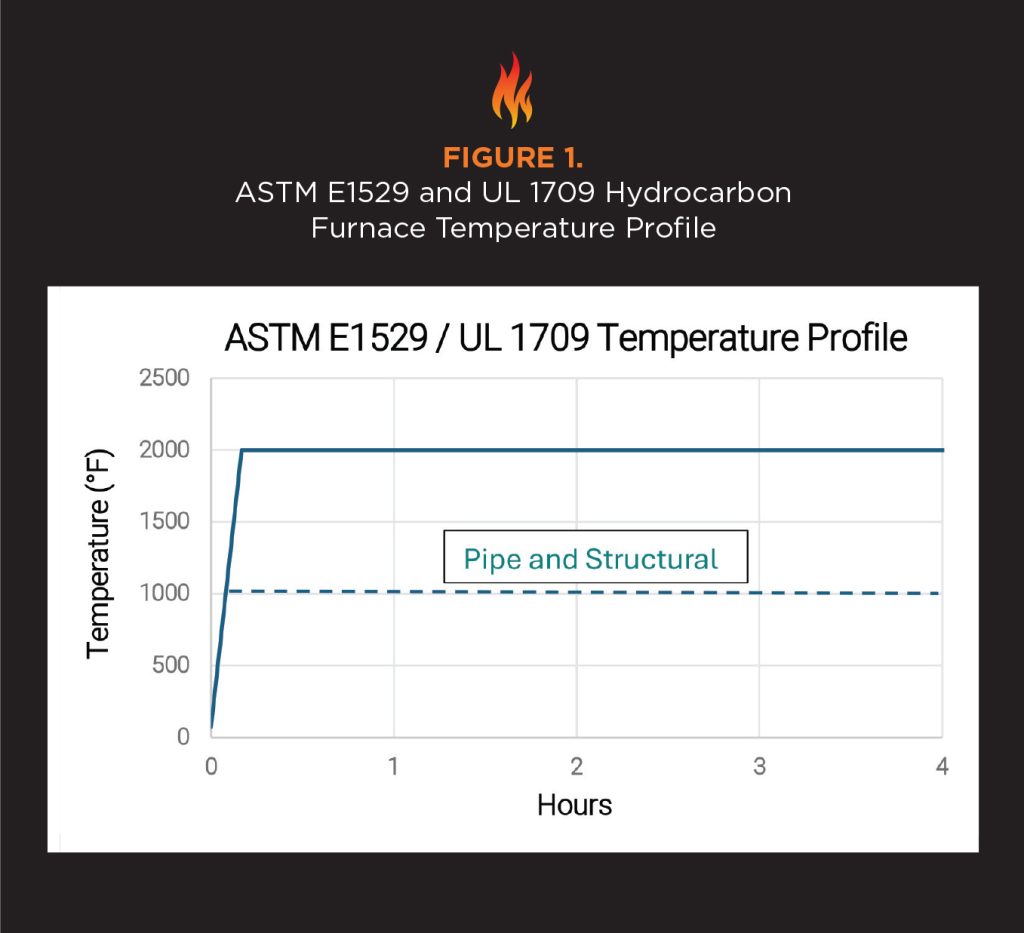

By contrast, ASTM E1529, Standard Test Methods for Determining Effects of Large Hydrocarbon Pool Fires on Structural Members and Assemblies, and UL 1709, Rapid Rise Fire Tests of Protection Materials for Structural Steel, use a hydrocarbon temperature profile (Figure 1), which is more aggressive. The furnace reaches 2,000°F in less than 10 minutes and is used primarily for industrial applications seen in refineries and petrochemical facilities.

Much like the previous ASTM/UL comparison, the test conditions are the same, but UL 1709 requires greater detail in describing the components used for the test.

The Purpose of ASTM E119 and UL 263 Fire Testing

ASTM E119 and UL 263 fire testing is designed to simulate real-world fire conditions in buildings—whether single-family homes, multi-family dwellings, or commercial structures. The test creates an extreme environment to evaluate the limits of a material or system under fire exposure.

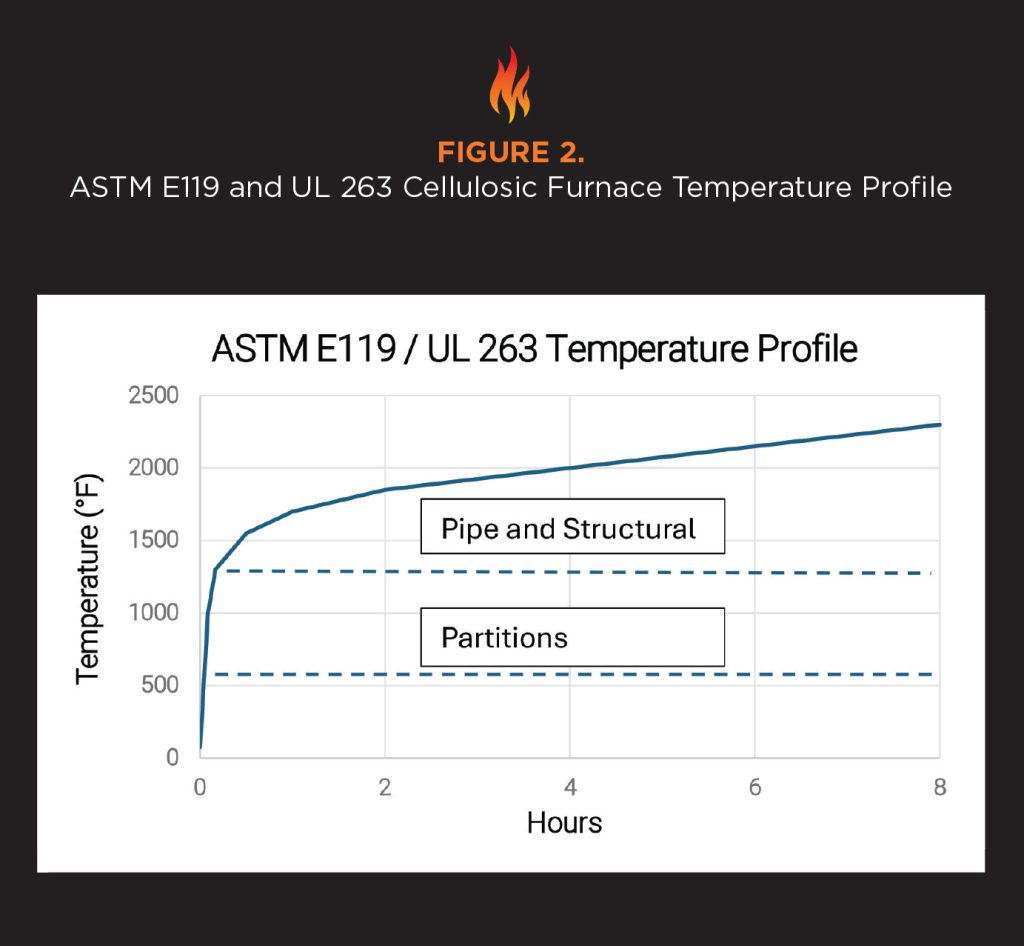

The furnace used in ASTM E119 and UL 263 testing follows a cellulosic temperature curve (Figure 2) that mimics the temperature rise expected in human-occupied spaces. This curve is gradual, reaching approximately 2,000°F over a 4-hour period.

Because these tests were designed to simulate a real-world situation, additional tests such as ASTM 814 and UL 1479 are required for components that penetrate the partition, such as piping, ducting, and electrical components.

Additionally, the joints in the partition construction must meet applicable standards, such

as ASTM E1966 and UL 2079. This testing ensures that joints and penetrations don’t become weak links in the partition.

Wall Partition Testing

Wall partitions are tested by constructing a wall between the furnace (exposed side) and the ambient laboratory environment (unexposed side). The furnace heats the exposed side according to the ASTM E119 profile. Meanwhile, thermocouples measure the temperature on the unexposed side.

The test continues until the temperature on the ambient side rises 250°F above the starting ambient temperature. For example, if the ambient laboratory environment starts at 75°F, the test ends when the unexposed side reaches 325°F.

To achieve a 2-hour rating, the wall must resist heat transfer for at least 2 hours without exceeding the temperature threshold.

Additional Requirements

- Cotton Pad Test: A small cotton pad (4” x 4” x ¾”) is placed over joints or penetrations. If hot gases ignite the pad, the system fails.

- Hose Stream Test: After fire exposure, the wall is subjected to a high-pressure water stream to simulate firefighting efforts. If the stream penetrates the wall, it fails.

Wall assemblies typically consist of wood or steel framing, with one or more layers of Type X gypsum board. Organizations like UL maintain directories of tested and approved wall systems.

Piping and Structural Steel Testing

Unlike wall partitions, piping and structural steel components are tested as stand-alone elements within a large-scale furnace for both E119 and UL 1709 fire tests. The goal is to determine how long insulation can delay heat ingress and prevent structural failure. The failure criteria are the same for both cellulosic (ASTM E119/UL 263) and hydrocarbon (ASTM E1529/ UL 1709) test methods.

Thermocouples measure the temperature of the steel.

The test ends when:

- The average temperature of the steel reaches 1,000°F, or

- Any single thermocouple reaches 1,200°F.

These thresholds are critical because steel loses approximately 50% of its strength at 1,000°F. Maintaining structural integrity during a fire is essential for occupant safety and building stability.

Factors Influencing Test Duration

- Mass and Surface Area: Heavier elements with smaller surface areas take longer to heat than lighter, thin-walled components.

- Insulation Type: High-temperature insulation materials, often paired with stainless-steel jacketing, are used to protect these elements. Assemblies also can include intumescent coatings or insulating sprays that contain gypsum or other insulating components (e.g., vermiculite, fibers) to slow down the passage of heat by charring and expanding to protect the structural steel.

- Installation Quality: Gaps, compression, and poor fit can reduce fire resistance.

- Test Method: For a given pipe or structural assembly, ASTM 1529 and UL 1709 testing will have lower hourly ratings than ASTM E119 and UL 263 test methods. ASTM 1529 and UL 1709 tests take less than 10 minutes to reach 2,000°F. ASTM E119 and UL 263 test methods have a slower heat-up, taking 2 hours to reach 2,000°F.

Why Fire Ratings Matter

Fire ratings are not just numbers—they represent the time a system can protect lives and property during a fire. In buildings, fire-rated partitions help contain fires to specific areas, giving occupants time to evacuate and firefighters time to respond. Insulated piping delays the heat-up of potentially flammable liquids and delays structural steel collapse, preserving escape routes and structural integrity.

Manufacturers invest heavily in fire testing to ensure their products meet safety standards. However, it’s crucial for end users to understand what the ratings mean and how they apply to their specific applications.

Common Misconceptions

- “This insulation has a 2-hour rating.” Not quite. The insulation itself doesn’t have a rating—the system it’s part of does. Ratings apply to tested assemblies, not individual

materials. - “Low flame spread means it’s fireproof.” Flame spread is just one aspect. It doesn’t guarantee non-combustibility or fire resistance.

- “All fire tests are the same.” Each test serves a different purpose. Understanding the distinctions is key to proper specification and compliance.

Conclusion

So, what’s the deal with hourly fire ratings? The answer requires understanding that fire safety is a multi-layered concept, with each testing standard serving a distinct purpose. These standards work together to create comprehensive fire protection strategies.

ASTM E84 and UL 723 tell us how quickly flames spread and how much smoke develops—critical for surface behavior in the early stages of fire. ASTM E136 and ISO 1182 determine whether a material is truly noncombustible and won’t contribute fuel to a fire. And ASTM E119, UL 263, ASTM E1529, and UL 1709 evaluate complete systems—not individual materials—to determine how long assemblies can resist fire under cellulosic or hydrocarbon exposure conditions.

Whether you’re designing wall partitions, insulating structural steel, or protecting piping systems, it’s essential to understand how fire tests work and what the results mean.

By recognizing the differences between flame spread, combustibility, and hourly ratings, engineers and specifiers can make informed decisions that enhance safety and performance. Fire testing is not just a regulatory hurdle—it’s a critical tool for safety and infrastructure.