Your Current Project May Be Out of Date Before the Client Moves In

The building industry is experiencing an accelerating pace of change around energy efficiency. Utility and fuel price volatility, coupled with efficiency initiatives from many sources, are driving changes at a rate that may make many building projects, currently under design, out of date before they are built. Architects must consider this trend as they choose whether to meet today’s standards or prepare for tomorrow by meeting insulation standards that are certain to exist in the near future.

The most immediate change is the release of the new edition of ASHRAE 90.1.1 The 2007 edition was published in January of 2008 containing significant increases in energy efficiency requirements. Originally scheduled for release in June of 2007, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) urged ASHRAE to delay publication so two addenda (one for opaque envelope components and another for fenestration) could be included to accelerate their contribution to national energy savings.

The 2007 standard will likely be referenced in the 2009 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) and then be considered for adoption by local code jurisdictions. Since many communities only adopt code updates in harmony with the three-year International Code Council (ICC) publication cycle, it was important to get the updated energy efficiency standard in place in time to make the 2009 edition of the IECC. All of this is happening in advance of the publication of ASHRAE 90.1?2010, which has the goal of achieving a 30-percent energy savings compared to the base ASHRAE 90.1?2004 edition. With energy codes changing rapidly, and with other sustainability initiatives gaining momentum daily, it makes sense to insulate at levels higher than code minimums so your project is not “energy-out-of-date” before the client moves in.

Sustainability and Energy Efficiency

In 2006 the American Institute of Architects issued its 2030 Challenge. It called for an aggressive and relentless improvement in energy efficiency until buildings become carbon neutral and do not use fossil fuel or greenhouse gas-emitting energy to operate by the year 2030. The Challenge was soon endorsed by the U.S. Conference of Mayors, and a host of agencies have pledged to help set the benchmark to measure improvement. This goal is very aggressive and will require significant innovations in the way buildings are built and operated. Buildings under design today are likely to still be in use in 2030. Therefore, it makes sense to consider future energy efficiency goals as you specify insulation today.

On another front, most green building initiatives place a high value on the role of energy efficiency. For example, Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) 2.0 is a green building rating program developed by the U.S. Green Building Council. It places a very high priority/reward on exceeding ASHRAE 90.1 minimum standards. During the design phase for projects, many design professionals consider the objectives of LEED, even if they do not plan to pursue LEED certification. So if a user couples rapidly advancing energy efficiency standards with the increasing prominence of LEED sustainability goals, it is not difficult to imagine that a current project may be “energy-out-of-date” before the client moves in.

It’s possible to prevent out-of-date projects and best serve building owners and occupants by anticipating changes that surely will only grow over time due to energy volatility and the associated increased energy costs. So position your client’s building for the market demands of the very near future by designing it to operate competitively with low energy costs.

From “Common Practice” to

“Investment Analysis”

Keep in mind that increased insulation requirements in codes and standards are not arbitrary or “nice to do”; they are justified by economic considerations. Higher levels of insulation are warranted by the cost of energy saved, which also translates into a lighter environmental footprint of the building. Let’s examine a brief history of energy code economics.

When the original “Standard 90” was developed in the mid-1970s, requirements were based on established or “common” construction practices. Within 10 years, all 50 states enacted regulations based on Standard 90. Throughout the 1980s, research continued in the areas of energy efficiency, fuel calculation techniques, and dynamics between various building components. All of those developments led to issuance of the first ASHRAE Standard 90.1 in 1989.

Drawing upon lessons learned and criticisms from the development of the initial standard, ASHRAE began early in 1990 to evaluate criteria for the next version of the standard. Two key decisions were made:

- Economics should be used as the basis for setting the criteria

- All sections of the new standard should apply the economic approach to ensure the standard is balanced among building components, such as envelope, lighting, and mechanical

The 1999 edition, as well as the subsequent 2004 and 2007 editions, was based on these two economic concepts.

In recent editions, ASHRAE 90.1 has used an “investment analysis” or an “investment approach” to calculate “optimum” insulation levels and establish those as the minimum levels. “Optimum” or “lowest life-cycle cost” insulation levels are calculated based on assumptions made about present and future market conditions (first cost of installed insulation, life-cycle cost of energy, present and future cost of money, etc.). One method to predict future trends is to plot past costs and project similar trends into the future. That method depends on fitting curves to historical data, which may lead to less accurate predictions because parts of the curve vary greatly in rate of change over the years as cost trends vary. Another method, the one adopted by ASHRAE, uses economic scalar ratios, which combine many complex variables and their historic fluctuations into a factor that simplifies the calculation and avoids the difficulty in selecting specific economic parameters for building components.

Scalar ratios expand the traditional

life-cycle cost concept of uniform present worth factors to account for non-uniform fuel escalation rates, discount rates, interest rates, and the benefits of state and federal tax deductions to commercial building owners.

Looking Ahead

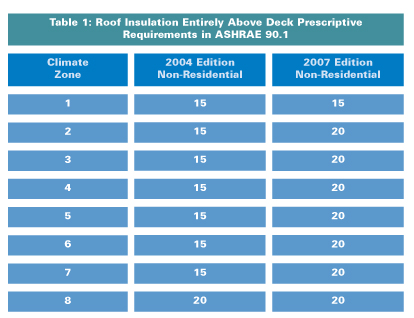

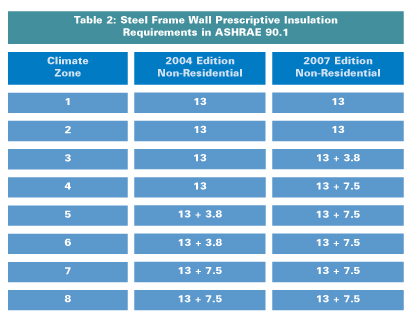

So what happens when the scalar approach is used to calculate the level of insulation justified by today’s energy costs and projections? ASHRAE has done just that for 90.1-2007, and the new standard will, in the prescriptive compliance path, call for additional roof insulation, increasing the minimum R-value in most geographic locations from R-15 to R-20. The prescription for continuous insulation (“ci”) over steel stud framing will geographically expand from only a portion of the United States to virtually the entire mainland and range from a minimum R-3.8 in some Southern and mid-state locations to R-7.5 in much of the United States and a minimum R 15.6 in the extreme North-Central region.

Figures 1 and 2 compare minimum roof and “ci” insulation requirements in 90.1?2004 and 90.1?2007.

Minimum versus Optimum

It is important to understand that energy codes are really minimums, and in many jurisdictions they are outdated, if adopted at all. Even though a project may meet the minimum energy code in a given location, the design might not be the best or most economic for the client because of rapidly changing economic conditions. The architect must make that determination.

Architects must ask themselves, “Is the minimum energy standard the most economic insulation level to serve my client best over the life of the building?” From an insulation perspective, the answer is clearly ?no.? And even if a design exceeds the current minimum standard, by the time the building is occupied it may only meet the minimum standard at that time.

It is best to at least meet the next minimum standard?ASHRAE 90.1?2007?because by the time the client moves in, rapidly changing energy standards may mean the building is already outdated.

Adding an inch of insulation to the roof or an inch of “ci” to the walls certainly won’t make a current project carbon neutral, but it is an important step toward meeting national energy conservation goals. The investment is justified by the additional cost savings, and it may keep the building from being out of date before it is occupied.