As of 2024, every major mechanical building code now requires insulation for ducts and/or piping in a plenum to be “listed” and “labeled.” Owners, engineers, and other specifiers are making changes to their HVAC and plumbing insulation specifications, and building code inspectors are taking a closer look at insulation, while the contractor or installer is a bit caught in the middle. Installers need to understand what the new language means to ensure the right product is installed in the right application to follow the specification and meet building codes to the satisfaction of the inspectors.

What Do “Listed” and “Labeled” Mean, and Why Does it Matter?

An insulation product is expected to meet certain standards in the building and construction industry. Within organizations like ASTM and UL there are standard specifications, which list all the tests a product is expected to undergo as a minimum industry standard; and there are standard test methods, which describe the details of the tests themselves.

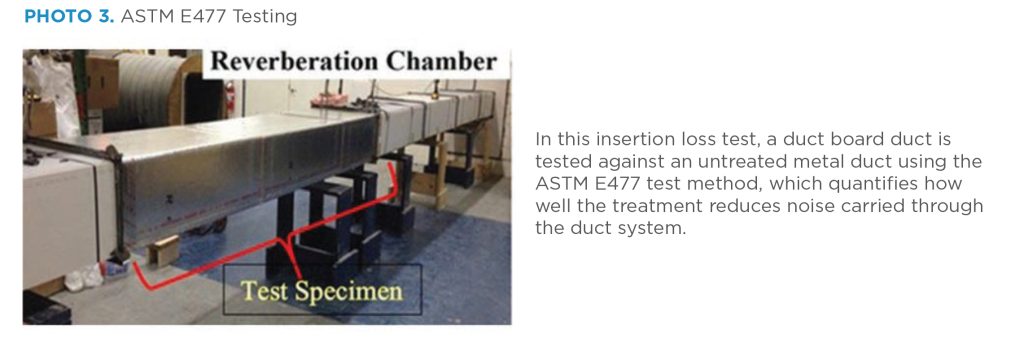

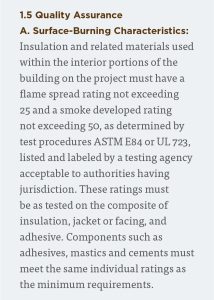

In the case of mechanical insulation, an insulation product could be tested to the “standard test method” per ASTM E84 or UL 723 for a flame spread rating and smoke developed rating, for example. The insulation sample would need to be mounted per ASTM practice ASTM E2231. If an insulation manufacturer wanted to show that their product met the minimum industry requirements, they would have a few ways of doing so.

One option is for the insulation manufacturer to test it internally— they may have a test chamber or test setup they can run themselves—and they would stand behind their own results. This would still be considered a test to the ASTM or UL standard as long as they followed the procedure outlined.

Another option is to obtain an independent third-party test, taking the testing out of the hands of the manufacturer and entrusting it to a testing lab. When going this route, manufacturers often look to labs that are accredited, meaning that that they have been recognized by OSHA as a nationally recognized testing laboratory (NRTL).

With either of these options, a manufacturer must only report the test results to show compliance with the standards. This is called self-reporting. How many times they test, or how often they test, is entirely up to the manufacturer.

Going a step further, the manufacturer can get the product “listed” and “labeled” by an NRTL, providing more confidence in the long-term performance of the product. “Listed” means that the NRTL will publish the test results publicly on its website and require regular testing to ensure that the product continues to meet the results listed. The product and associated materials will also be “labeled” with the corresponding test report number that links it to the test report and shows that the testing is continuously maintained.

What Exactly Are the New Building Code Requirements?

Updates to the International Mechanical Code

The International Code Council was an early adopter of the terms “listed” and “labeled” for insulation in plenums, including them in the International Mechanical Code (IMC) as early as 2012. For example, Section 602.2.1, entitled “Materials within Plenums,” requires, with few exceptions, that anything in a plenum either be noncombustible or be listed and labeled as having a flame spread of no more than 25 and a smoke developed index of no more than 50 when tested to ASTM E84 or UL723. The section for duct coverings and linings, like duct insulation, also included 25 flame spread and 50 smoke development requirements with the sentence, “Coverings and linings shall be listed and labeled.” Piping systems in a plenum would still be interpreted as falling under the broader category of “materials in plenums,” but neither piping nor piping insulation was specifically called out.

The IMC was again updated in 2015, and more clarification was given to exactly what did and what did not have to be “listed” and “labeled” to meet the flame spread and smoke developed requirements. The “Materials within Plenums” section remained unchanged, but new sections were added that covered specific materials and their requirements. For example, a new section was added in 602.2.1.7 for “Plastic Plumbing Pipe and Tube,” which clarifies that plastic piping itself must be listed and labeled to ASTM E84 or UL 723.

In the 2018 version of the IMC, a new section was added for 602.2.1.8 specifically addressing “Pipe and Duct Insulation within Plenums,” clearly stating that the insulation in plenums, whether for a pipe or duct, must meet the requirement of no more than 25 flame spread and 50 smoke developed per ASTM E84 or UL 723, and describing the mounting method and additional testing criteria. There is little ambiguity in the phrase, “Pipe and duct insulation shall be listed and labeled.”

The 2024 IMC brought in a lot of new, helpful language, including detailed descriptions of what qualifies as a plenum and the various types of plenums the section applies to. Section 602.3, “Materials within Plenums,” is reduced to just a single sentence, referencing the subsections below. The subsections call out each and every material likely to be found within a plenum. One exception is “materials listed and labeled for installation within a plenum and listed for the application.” Among the following subsections are “Plastic Piping and Tubing” and “Pipe and Duct Insulation within Plenums.” Just for good measure, a new Section 602.3.10, titled “Other Combustible Materials,” is included as a catch-all, simply stating that any combustible materials in a plenum not specifically mentioned in the sections above must be listed and labeled as having no more than 25 flame spread and 50 smoke developed per ASTM E84 or UL723.

Updates to the Uniform Mechanical Code

The IMC is not the only mechanical code adopted by states and municipalities across the United States. While most states have adopted some version of the IMC, there are some states and municipalities that have opted to use the Uniform Mechanical Code (UMC) as the reference for their code instead, like the State of California. Additionally, there are some cities or municipalities that have chosen to adopt the UMC even if the state has adopted the IMC. For example, the City of Houston uses the UMC, even though the State of Texas has adopted the IMC. For this reason, the different codes try to mirror each other, eventually using similar language to reduce chaos and confusion in the industry.

The 2024 UMC had the first mention of “listed” and “labeled” regarding insulation in plenums, adopting similar language to what was found in the IMC at the time. Similar to the IMC, Chapter 6 of the UMC also covers duct systems and plenums.

The UMC also has a Section 605, “Insulation of Ducts,” in which the final sentence clearly states, “The duct coverings and linings shall be listed and labeled.” Understandably, the chapter on “Duct Systems” focuses more on duct insulation than piping insulation, as seen in earlier editions of the IMC. So far, this is the only mention in the UMC of insulation needing to be listed and labeled.

As of 2024, the UMC does not specifically require listed and labeled for insulation on piping. Section 1201.2 states, “Where installed in a plenum, the insulation, jackets, and lap-seal adhesives, including pipe coverings and linings, shall have a flame-spread index not to exceed 25 and a smoke-developed index not to exceed 50…” So here we are told that the insulation must be tested to ASTM E84 or UL 723 and meet the same 25 and 50 ratings, but self-reported testing is acceptable.

That being said, a project specification might not rely solely on the IMC or UMC with regards to HVAC and mechanical systems—especially if the specifier does work in multiple jurisdictions. In addition to the requisite mechanical code, many local and state jurisdictions also require compliance with the standards set by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA).

Updates to National Fire Protection Association Standards 90A and 90B

The NFPA has its own series of standards for the building and construction industry. Specifically, NFPA Standard 90A—the Standard for Installation of Air-Conditioning and Ventilating Systems—and NFPA 90B—Standard for the Installation of Warm Air Heating and Air-Conditioning Systems—are often cited regarding fire safety for HVAC systems.

In the committee to consider updates and changes for the 2024 edition, a suggestion was submitted through public comment that pipe and duct insulation should be listed and labeled so that NFPA codes and standards would agree with the other codes and standards. This also would be consistent with other items in plenums, like equipment and piping, that NFPA already required to be listed and labeled. The committee agreed and adopted the new language for the 2024 edition.

Section 6.4.1 is the section that specifically addresses pipe and duct insulation, calling for the insulation to have a maximum flame spread of 25 and maximum smoke developed of 50 when tested to ASTM E84 or UL 723. A subsection was added (6.4.1.1), with the single line, “Pipe and duct insulation shall be listed and labeled,” bringing the NFPA standard in line with the other major codes.

How Does the Change Affect Specifiers and Contractors?

Adding the words “listed” and “labeled” may seem like a simple change, but many separate project specification sections will be affected, including “Plumbing Piping Insulation,” “HVAC Piping Insulation,” “HVAC Equipment Insulation,” “Duct Insulation,” “Metal Ducts,” and practically any other mechanical or plumbing specification section that could conceivably have insulation in a plenum space.

Regardless of the section, project specifications generally list the flame spread and smoke developed requirements in the Quality Assurance paragraph. While some specifiers list one set of standards for insulation installed indoors and another standard for insulation installed outdoors—or inside plenums or outside of plenums—it is most common for specifiers to simply hold all mechanical and plumbing insulation to the highest standard and require all HVAC and plumbing insulation to be approved for use in plenums. Just as adding the words “listed” and “labeled” was a subtle but significant change to the recent codes, the words almost might go unnoticed by a contractor bidding on the project who is unfamiliar with the change.

It’s halfway down the paragraph, buried in a section so common it’s practically boilerplate. While “listed” and “labeled” can very easily be added to a specification, it is no good if the updates to the specification are completely missed by the contractor tasked with implementing it. There is a reason a specifier goes to the trouble of spelling everything out, rather than only stating something like, “product shall meet applicable building codes.” The specification change should do more to be noticed. Approaches like bolding, italicizing, underlining, or even highlighting important words in a different color may work, but a simpler solution may just be in the formatting. For example, consider adding a new sub-paragraph, or even just a single line, as in the update from NFPA 90A. See what such a formatting change does to the same example paragraph cited at left:

While simply adding the words “listed” and “labeled” might be enough to bring the project specification into code compliance, the contractor or installer needs to understand the change so as not to be blindsided by suddenly needing a different insulation product than the one originally bid—or, even worse, not realizing the wrong product was installed until the inspector reviews the work.

How Can We Help Building Inspectors Find What They’re Looking For?

Different states and cities have been operating on a patchwork of building codes and standards for years, making the job of the building inspector that much more difficult in trying to keep up with the codes and standards on a national, state, and even local level.

With the listed and labeled language update now in all major building codes and standards, there is more consistency in the industry—for example, eliminating the difficulty of not knowing whether to enforce an insulation requirement in the IMC that isn’t in the UMC or NFPA 90A. Just having the agencies in agreement on one more item, one more standard that is universally enforceable, makes the job easier. It’s no wonder the issue is getting more attention now!

Requiring a product to be listed and labeled is one thing, but expecting a building code inspector to read the fine print on a 1-inch tube of insulation hanging 20 feet in the air is quite another. The “labeled” part of “listed and labeled” means that the insulation itself should carry the seal, stamp, or other identifying mark from the nationally recognized laboratory that listed it. But, understandably, the insulation might be difficult to read.

It’s in the best interest of the insulation manufacturers to make their products easy to identify to ensure the right products are used in the right places. That might mean using dramatically different packaging, or a large, clearly identifiable label; or printing the label indicating the listing not just on every package, but on every brochure, invoice, product description, and other piece of literature in the contractor’s hands. One manufacturer has gone the extra mile by making the pipe and duct insulation approved for use in plenums a dramatically different color, easily identifiable from a distance.

What Do We Need to Do Now?

Not every product that has been used before can be used now. “Listed and labeled” is not simply a higher standard, but also higher accountability. Some legacy piping insulation may be perfectly fine for domestic plumbing running through a wall, or refrigerant piping in a variable refrigerant flow system, or underground buried lines; but if it’s not listed and labeled, it may not be permitted in a plenum. For insulated ducts, or any piping that could run through a plenum, it should be listed and labeled. So, what now?

The Role of Each Value Chain Player

Now, manufacturers need to rise to the challenge and make sure their insulation is up to the standards. Then, they must make sure the listed and labeled products are easily identifiable so they will not be confused with legacy products.

Specifiers need to make updates to their specifications—not just adding the listed and labeled requirements, but also ensuring the products they call out in the insulation schedule meet current code, verifying the building code requirements of the jurisdiction where the project is being performed with the authority having jurisdiction.

Contractors and insulation installers need to make sure they understand the changes to the specification language and are bidding and installing the appropriate products in plenum spaces.

Now, inspectors need to know how to identify the listed and labeled products. If the insulation isn’t easily identifiable at a distance, then they must know what else to look for (packaging, paperwork, etc.). Of course, there will still be times when a closer look is required.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, it is in everyone’s best interest to make sure that the insulation products that are installed in ducts and plenum spaces are up to the latest fire and smoke standards. The codes are evolving to meet higher standards, and no matter what your role is in the insulation industry—from manufacturer to specifier to contractor to inspector—it’s up to all of us to rise to the challenge.