Every once in a while, it is productive to review thermal insulation basics. There are several reasons for doing this. As contractors competitively bid material and labor on insulation jobs, and distributors and manufacturers provide prices and schedules for deliveries and address performance questions, it is easy to lose track of why the customer is purchasing insulation in the first place. Insulation users can become so accustomed to seeing particular insulation and accessory materials used in certain applications that they never question whether other materials would do just as well. Users also can become so pressured to reduce cost and speed up the schedule on a project that they accept an alternate material that is unsuitable (because of an increased safety risk, for example).

This article is the first in a two-part series, and its purpose is to remind readers of why the proper installation and maintenance of mechanical insulation is important. A follow-up article in the December issue of Insulation Outlook will take a closer look at the installation and maintenance processes.

The National Insulation Association’s (NIA’s) National Insulation Training Program (NITP) is an excellent way to brush up on the basics of insulation. Most insulation users have specialized knowledge. For example, if they work for an industrial insulation contractor, they may not have much experience with insulating commercial building heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems. If they work for a manufacturer, they may know a great deal about the product that manufacturer makes but not much about other products that are used in totally different applications. Unless they work for a contractor, they may not know much about installation rates and the factors that affect installation rates and times. If they do work for a contractor, they may not know much about insulation systems’ design and the selection of insulation materials; they just bid what is specified. The NITP rounds out a user’s knowledge base, filling in the gaps.

Basic Insulation Science

The first module in the NITP introduces students to the technology of insulation. The following definition is given for “insulate.”

Insulate (verb): To prevent the passage of heat, electricity, or sound into or out of an area; accomplished by surrounding an area with a non-conducting material.

For thermal insulation, which prevents the passage of heat, a non-conducting material is one that does not conduct heat well. The definition says nothing about using reflective surfaces to prevent the passage of heat. By this definition, a reflective or low-emittance sheet does not insulate. It may effectively prevent the passage of solar heat or reduce the emittance of heat; however, that does not make it a thermal insulation material. This distinction is basic to understanding what it means to insulate—in this case, to thermally insulate.

The NITP defines “thermal energy” and the transfer of that energy. Further, it defines a British thermal unit (Btu) as approximately the amount of energy released by burning a single wooden match, which explains why Btu quantities are so large (for example, there are 1,023 Btus in a single cubic foot of natural gas, and a million Btus of natural gas cost about $10).

In the Basic Insulation Science module, the NITP also covers the three modes of heat transfer: conduction, convection, and radiation. All three modes take place simultaneously within a thermal insulation material.

If users limit only one of these modes, such as with radiation when using a radiant barrier, they are not really using thermal insulation. Thermal insulation limits all three modes of heat transfer to one extent or another. This is not to say that a radiant barrier cannot be effectively applied to reduce energy use in certain applications, but it is not a form of thermal insulation. Likewise, a shiny vapor retarder may reduce convection within fibrous insulation and simultaneously reduce radiation heat loss or heat gain from a surface. That is usually beneficial. However, this performance does not make a shiny vapor retarder a form of thermal insulation because it does nothing, by itself, to reduce conduction heat transfer. This is a key point for understanding how thermal insulation works and what distinguishes a thermal insulation material from other materials.

The NITP also defines “K-Value,” or thermal conductivity. For a thermal insulation material, the value is low in comparison to other solid materials like steel, concrete, ice, and wood. While there is no official maximum value for a thermal insulation material, generally a value of less than 0.5 Btu-in/hr-ft2-°F, at room temperature, is used to distinguish a thermal insulation material from a non-thermal insulation material. According to the NITP, 1 Btu-in/hr-ft2-°F is a good upper limit at room temperature (75°F mean) for a thermal insulation material.

The NITP also discusses “R-Value.” For a flat material, this is simply determined by taking the reciprocal of the K-Value (1/k-value) for a 1-inch thickness at some particular mean temperature. The R-Value for 2 inches would be about double that for 1 inch, the R-Value for 3 inches would be about triple that for 1 inch, etc.

The NITP also mentions “U-Value” but does not go into how to calculate it. This is because calculating the U-Value can be complicated, as it considers an insulation system, including any gaps, structural thermal bridges, and other details that may increase heat loss or heat gain. The lower the U-Value, the less the heat loss or heat gain. The higher the U-Value, the greater the heat loss or heat gain and the greater the energy use, everything else being equal. For example, for a metal building insulated with metal building insulation, the U-Value determination includes the effect of the fiberglass insulation blankets being full thickness in some areas but compressed at the purlins. It also includes the insulating effect of the air films below and above the roof. The sheet metal roof material does not measurably contribute to the U-Value since it has no effective insulating capability. If the metal roof has a shiny, low-emittance surface in one case and a black, high-emittance surface in another, this property will have a small effect on reducing the U-Value in the first case. It will not be a large impact, however, assuming the fiberglass insulation batt has a significant thickness (several inches). Again, the paint used on the surface of the metal building roof is not a thermal insulation material because it does not simultaneously restrict conduction, convection, and radiation heat transfer through itself.

The NITP also discusses temperature. There must be a temperature difference for thermal insulation to perform its function. If there is no temperature difference, then insulation will not insulate. If it blocks or reflects sunlight, that may reduce energy use in a particular application. However, reflecting sunlight does not make the material thermal insulation. Reducing heat loss or heat gain where there is a temperature difference is another basic principle to the function of thermal insulation.

The next NITP topics are relative humidity and water vapor pressure. Moisture condensation problems on a chilled duct or chilled water line are common—particularly in the southeastern United States, which has a semitropical climate much of the year. Reasons for condensation problems can include faulty design, poor choice or quality of materials, poor installation quality, poor insulation maintenance, or some combination of these factors.

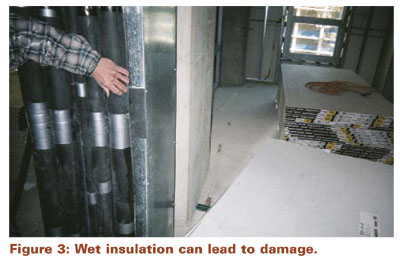

Just as water always flows downhill unless restrained from doing so, water vapor always will migrate from zones of high vapor pressure to zones of low vapor pressure unless restrained from doing so. Warm, high relative humidity zones have a high vapor pressure, and those with cold surfaces have a low vapor pressure. Those cold surfaces are where vapor condensation and water problems occur. Understanding relative humidity and water vapor pressure, and preventing water vapor migration, is critical to insulation system performance on cold systems. This is true whether one is designing the insulation system, manufacturing and distributing the materials used in the insulation system, installing those materials, or maintaining the insulation system. The consequences of not adequately addressing vapor pressure differences can be excessive condensation that leads to water damage of equipment, corrosion of structural members, damage to building materials, and mold growth. The consequences of water condensation problems are expensive to repair.

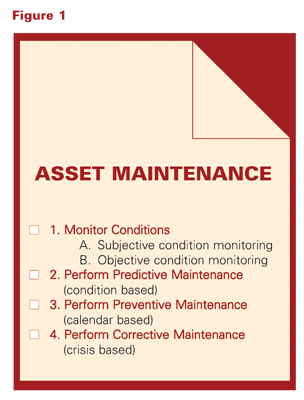

With this introduction to how insulation and insulation systems work, the NITP addresses the following basic reasons for insulating:

- To reduce energy costs

- To enhance process performance

- To reduce emissions

- To protect personnel

- To provide freeze protection

- To prevent condensation on the insulation system surface

- To reduce noise levels

- To maximize return on investment (ROI)

Thermal insulation can accomplish much of this. The level of importance varies from project to project.

System Design and Materials

It is useful for material manufacturers, distributors, and contractors to understand how engineers design an insulation system and select the appropriate materials for a particular project. Designers should follow some basic principles. First, they consider what they are insulating (a pipe, tank, vessel, etc.). Then they look at the nature of the process (high temperature, low temperature, near-ambient temperature, etc.). They consider the primary reason for insulating. Of course, they need to know the design conditions (service temperature, ambient temperature, etc.) and the design criteria. The following questions need to be addressed before designing a system and specifying materials:

- Is weather protection required (is it indoors or outdoors)?

- Are there any codes that need to be met?

- Is there a particular need to prevent the occurrence of corrosion under insulation (CUI)?

- Is there a need to use non-combustible insulation?

- Is personnel protection required?

- Will the insulation material be subjected to physical abuse and/or vibration, requiring it to have a high compressive strength?

- Does the system need to block the transmission of sound?

- What ROI is required over time?

- How long must the system last?

If there is an older specification available, the designer must review it in detail to ensure that it addresses all of the above issues. If not, it will need to be updated.

The primary types of thermal insulation are fibrous, granular, and cellular. There are also different materials within each type (fiberglass, mineral wool, calcium silicate, perlite, cellular glass, polystyrene, polyisocyanurate, etc.), and each material has different properties. One of the most valuable parts of the NITP is being able to see and handle samples of dozens of different insulation materials and insulation accessories.

The NITP also discusses the different temperature ranges: the cryogenic range (below -100°F); the thermal range (from -100° to 1,200°F); and the refractory range (above 1,200°F). These are important to understand because every material has upper and lower temperature limits, beyond which it is no longer suitable for use. It is also important to understand what causes those limits (linear shrinkage, melting, flaming, exotherming out of control, etc.). If contractors and distributors understand these limitations, they will no longer suggest that customers use insulation materials in unsuitable temperature ranges.

Different insulation materials are available in different forms. For example, some are only available as rigid boards or blocks and/or rigid preformed pipe shapes; others are only available as flexible, resilient blankets. The form has a significant impact on how materials are installed and what the installation productivity will be.

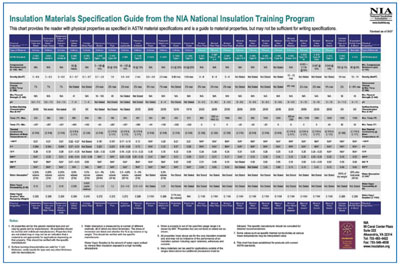

NIA’s Insulation Materials Specification Guide (see Figure 5) is a large table that summarizes insulation materials by American Society of Testing and Materials (ASTM) specification and properties (maximum temperature, minimum temperature, density, pH, compressive strength, and thermal conductivities). While this table is not a design tool, it serves as a quick reference to determine the properties of specific insulation materials, as well as which ASTM specification covers each material. (To download a PDF version of the guide, please visit www.insulation.org/techs/insulation-materials-specification-guide.cfm.)

The materials have many different mechanical and chemical properties. For example, some rigid materials have high compressive strength and can take more physical abuse and vibration than others. Some absorb water readily, requiring extra attention to keep them dry. Others, by contrast, have hydrophobe in their chemistry and can resist water absorption. Some have corrosion inhibitors added during their manufacture to reduce the probability of CUI (on carbon steel surfaces) or stress corrosion cracking (on stainless steel surfaces).

Some insulation materials and accessories are attacked by certain chemicals, such as strong acids, strong bases, or liquid hydrocarbons. Some burn readily and will support combustion, some will not support combustion but are still rated as combustible per the test for combustibility, and some will neither support combustion nor be rated as combustible. All of this should be understood well by those working with mechanical insulation.

There is a long list of considerations and possible requirements for jacketing and accessory materials, including the following:

- Do they need to resist weather exposure?

- Are there certain chemicals they must resist?

- Should they be able to withstand fire?

- Should they have a low emittance?

- Should they be abuse resistant?

Insulation Thickness Determination

The 3E Plus® software program continues to serve the insulation industry, as well as purchasers and specifiers of mechanical insulation. The program is maintained by the North American Insulation Manufacturers Association (NAIMA) and is updated regularly.

While the program includes a data file of thermal curves for many different materials, per the appropriate ASTM material specification, students are encouraged to input manufacturers’ thermal conductivity data taken from product data sheets. The computer program can be extremely valuable in the hands of skilled users, allowing them to determine the required insulation thickness for a job (whether for energy savings, condensation control, process control, or personnel protection); estimate the reduction in air pollutants; and estimate the value of the energy savings in dollars.

To learn about NIA’s 3E Plus training program, please visit www.insulation.org/training/seminar. The NIA’s Insulation Energy Appraisal Program (IEAP) also covers 3E Plus. The software program is a useful and powerful tool for engineers, facility owners, material manufacturers, distributors, contractors, and government officials.

The Bottom Line

In the NITP, and in working with mechanical insulation in general, it is important to remember that thermal insulation has a synergistic effect on many areas of a facility, including the following:

- Energy cost

- Production quality

- Worker comfort

- Worker safety

- Process stability

- Facility emissions

- Facility maintenance

While there is substantial overlap where different types of insulation materials are suitable, no two types are exactly the same. Each has its strengths and limitations. Still, each type of mechanical insulation has one thing in common: Correctly designed and installed as part of a system, it provides a cost-effective solution to excess heat loss or heat gain.

When the mechanical insulation basics are followed, an insulation system reduces energy use; provides process control, personnel protection (on hot systems), and condensation control (on cold systems); reduces emissions; and lasts 20 to 25 years. As with most things in life, it pays to do things right the first time and then take care of them over time.